Coming out of prison

Department of Corrections joins with re-entry organization to simulate resources

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook Staff Writer

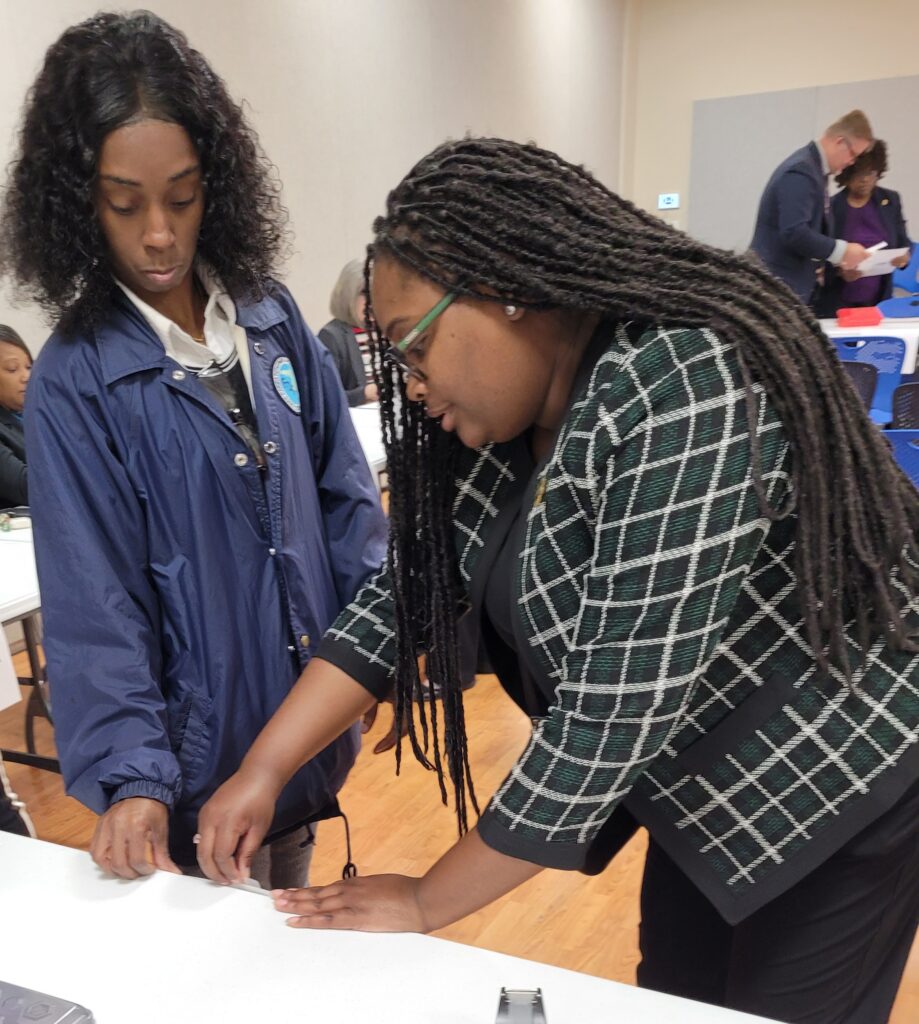

An unidentified criminal offender goes through a re-entry interview as part of being released from prison. The process includes a lot of paperwork and the offender leaves with a large manila envelope.

The most important thing in the packet is known as a “life card.” In layman’s terms, it’s the former offender’s manual for successfully navigating the re-entry process.

About 40 participants filled into a room at the Leroy Collins Library last Thursday to simulate what the re-entry process is like. The simulation was carried out by a group made up mostly of Department of Corrections personnel providing several of the resources that the ex-offender will need to avoid recidivating.

The Big Bend AFTER Reentry Coalition collaborated with the Florida Department of Corrections to go public with the re-entry simulation.

Using Corrections personnel for the simulation was essential, organizers said, because it gives them an up-close look at what an ex-offender faces after spending time in prison.

It’s “a real hands-on understanding of how challenging re-entry is for people coming on this program,” said Anne Meisenzahl, who chairs the Big Bend AFTER Reentry Coalition. “We sometimes think how hard can it be; come back to society, get a job and start your life over.

“But what we don’t often realize is that when you come out of prison without identification, no money in your pocket, you don’t want to go back home and live with your brother or your mother because that’s the neighborhood where you got into trouble in the first place.”

Ex-offenders aren’t completely down and out when they leave prison, as illustrated during the simulation. The mock session included stations that simulated church, work, bank, super center and several other resources.

Drug testing and required visits with probation officers are among the must-do. Ex-offenders are also required to carry three forms of identification and a transportation ticket. They will also have to means to get $25 each time for selling plasma up to twice each week.

Each of those services is expected to be completed over a four-week period. The group went through an exercise of following the life card, some finding it difficult to keep up with.

For example, at the end of the first week some participants said accessing the resource they needed left them feeling frustrated, violated and hungry. After the second week, some of them found themselves homeless.

Facilitator Amy Frizzell, a former warden at Polk County Corrections facility who is now an assistant director of programs in Region 1, said the Department of Corrections is making the simulations a priority. It is essential to helping resource personnel be more empathetic toward ex-offenders trying to restart their lives, she said.

However, she said some former inmates struggle to handle re-entry. Many of them end back up in prison, she said.

“Recidivism is a real problem and that is why we are here today,” Frizzell said. “That is something that we work on every single day. We never want to see a man or a women return to prison. However, it does occur for some reason.”

The simulation was a first-time experience for Felecia Dixon-Richardson, a professor of criminology at FAMU. She participated in the role of an ex-offender.

She plans to share the experience with her students at FAMU, Dixon-Richardson said.

“It’s a great demonstration of what offenders actually go through when they are released from prison,” she said. “You can watch movies, read about it but to actually see the stumbling blocks along the way, it shows it’s extremely difficult sometimes.”

Some of the barriers were too much for Rose Alexandre, who works as an educator with inmates. She also came away understanding how a formerly incarcerated person could become frustrated during re-entry.

It left her asking questions.

“Whatever society has going on, why do I have to suffer?” a former inmate might be asking, she said. “It makes me want to even get my church involved to start a prison ministry. This has opened my eyes to what the community could do, but we can’t really rely strictly on the government for help.”