Robinson’s path to FAMU interim president started at an early age

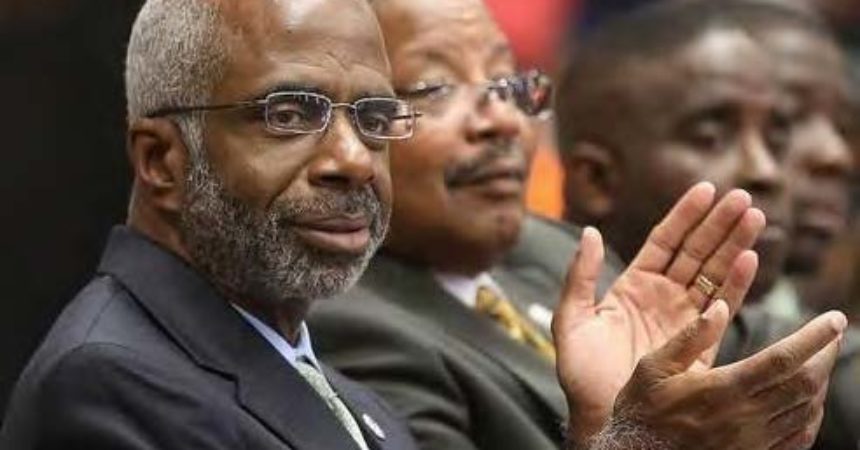

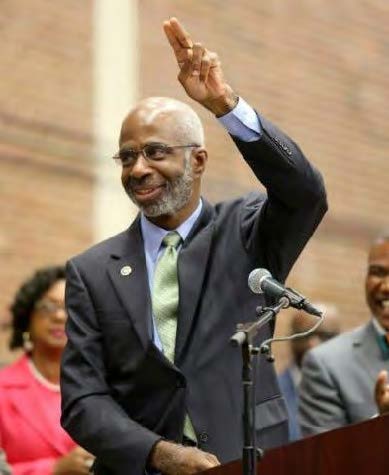

Larry Robinson, who has a long list of achievements as a scientist, is getting plenty of endorsements to be the next president of FAMU.

Photo courtesy FAMU

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook staff writer

The day the Florida A&M University Board of Trustees decided to give Larry Robinson his third stint as interim president of the university, the announcement was greeted with cheers.

Robinson had all of the credentials, having been associated with FAMU as faculty, serving as provost and taking the lead in the development of the school’s Environmental Science Institute. His commitment to the university also figured into the decision, according to members of the board, who also were impressed with his methodical way of making decisions.

On top of that, Robinson is known as one of the nation’s leading figures in chemistry and the study of nuclear science.

For all that he has achieved as an educator and scientist, Robinson has been selected as Capital Outlook’s Person of the Year.

“He is very professional and thought-minded when it comes down to the institution and that’s what we need, in my opinion, to go to the next level,” said Robert Woody, a member of the FAMU BOT. “We needed to have someone who would come in, have the respect of the FAMU family, have the respect of the folks downtown, the governor and board of directors as well as political friends on both sides of the aisle. We thought he was the perfect person for it.”

Those same traits were obvious when former FAMU president Frederick Humphries hired Robinson in 1997 to lead the development of the school’s Environment Science Institute. Robinson went on to hold several titles at FAMU, including two previous stints as interim president.

Robinson hasn’t indicated whether he’d like to have the president’s role permanently, but Humphries and others who know him say he would be the right fit.

Since becoming interim president last year, Robinson has made several personnel changes. Recently, he named Barbara Cohen-Pippin to succeed Tola Thompson as the university’s liaison with the Florida Legislature. Thompson left FAMU to become chief of staff for U.S. Rep. Al Lawson in Washington.

He is expected to make another major hire shortly as he has to replace chief legal officer Maria Feeley, who stepped down to take a position at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.

Robinson also has his fingers on the pulse of the development of Tallahassee’s south side where the university is located. He said he’d like FAMU to have a say-so in any development in the area because of how it could impact the university.

Robinson’s days at FAMU are hectic, but he finds his reprieve in time spent with his wife, Sharon. The couple car-pools to work a few times each week – Sharon is a physical therapist at Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare – which has been good for their marriage of 32 years.

“During that time, we get a lot of good conversation in,” he said. “Those are very important moments as well.”

Running, an exercise to which he took a liking in high school, also is therapeutic for him, Robinson said.

“As long as I’m healthy, that’s what I turn to,” said Robinson, who runs a couple of miles at a time, as often as he can. “I can get my thoughts together. It allows me to dissipate the stress through running. That’s a deep stress reliever.”

The level of commitment that Robinson is demonstrating in his personal and professional life is rooted in his upbringing on the south side of Memphis, Tenn. As the third of six children, raised by a divorced mother, he watched his two older siblings attain academic and professional success.

Robinson decided to emulate them. The business owners, bankers and other professionals that he saw in his community also made an impression on him. All those examples, Robinson said, planted a seed that led to him being curious about how successful people are molded.

Yet no one had as much influence on the path Robinson has taken like his mother and grandmother.

The neighborhood where Robinson grew up in Memphis has undergone what he calls “a major transformation” from the days when there were plenty of positive influences.

“Everybody you encountered had big dreams; big plans,” Robinson said. “All of those characters in the community were supportive and were people thought to be bigger than their circumstances. All of those factors contributed to me developing a belief in my ability to become anything that I endeavored to become.”

His mother was constantly driving that home and she never let him falter. Like the time in middle school when Robinson thought he had a shot at becoming a basketball player and was seemingly on his way to making the team. He recalled how he made a shot that might have convinced the coach that he was worthy of being chosen from the other prospects in the crowded gym.

It was right after making that shot that he surprisingly noticed his music teacher and mother, who he didn’t tell he was trying out for the team, sitting in the stands. She immediately informed him that he’d taken his last shot as a basketball player.

His mother insisted he pursue music like his older brother who played the French horn and a sister who played the flute. Robinson became a percussionist and to this day still has a pad and a pair of sticks that he bangs on occasionally.

All the time he played the drums, Robinson had a sense of wanting to know how things worked, especially when it came to the environment. He soon found himself delving into some of the chemistry and calculus books his older brother had left behind.

Fascinated with math and later a curiosity to know how nuclear science could be used positively such as in medicine, he began to investigate and eventually developed a liking for chemistry.

“It was very attractive to me,” Robinson said.

Indeed. So much so that he emerged as a scientist in demand for some well-publicized projects.

When there were doubts about how former President Zachary Taylor died after only a year in office (1849-1850), Robinson was chosen to be part of the team of scientists at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory who examined the exhumed body. They eventually found Taylor’s death wasn’t caused by deliberate arsenic poisoning – but rather acute gastroenteritis and poor medical care — answering a question that had lingered since Taylor’s death on July 9, 1850.

Robinson’s role in the investigation was one of the factors that led Humphries to hire Robinson in 1997 to lead the development of the school’s Environment Science Institute. Humphries resigned as FAMU president in 2003, but the two men have remained close friends.

Obviously, Robinson has Humphries’ endorsement should he decide to apply to become FAMU’s next permanent president.

“You have to be analytical and show you can solve problems,” Humphries said. “I think he has demonstrated that. A plethora of things were facing the university and he just ticked them off and got them done and put the university in better shape.”

Humphries has concerns that being interim president could affect how Robinson gets support for the university. But his belief in the university is strong enough to push through his agenda with politicians, Humphries said.

Humphries applauded Robinson for wanting to get the university involved in the development of the south side. He was especially concerned about a planned development around Cascades Park, not far from FAMU’s campus.

“I think it should depend largely on what FAMU says is important to put there. I mean, don’t do damage to us.” Humphries said, pointing to residential development south of Orange Avenue due to FAMU’s growth. Further development of the Adams and Monroe streets corridor is important to FAMU, he said.

“There are good ideas from the university about what should be put there. I hope the city would involve the university in the planning and development of that area.”

As time consuming as his responsibilities at FAMU can be, Robinson finds time to encourage high school students to consider a career in science. One of his biggest challenges, though, is dispelling the myth that only naturally brilliant people get to where he is in science.

Just recently, Robinson said, he told a group of teenagers that is not so.

“Everybody in this room has the intrinsic ability to do well in chemistry, calculus, physics or anything else,” he told the students. “It’s a matter of how hard you apply yourself to be more persistent than the next person is.

“Nobody is born knowing math, chemistry, biology and physics. However, you night have a tendency to absorb it quicker if you have committed yourself to doing so.”