Twenty cents! Two dimes! The 1956 Tallahassee Bus Boycott

By Gerald Ensley

Special to the Outlook

Twenty cents. Two dimes.

That’s what it cost to start the 1956 Tallahassee bus boycott.

On May 26, 1956, two Florida A&M students, Carrie Patterson and Wilhemina Jakes, boarded a Tallahassee city bus on South Adams Street. The two students paid their dime apiece fares – and plopped down on a front bench seat behind the driver next to a White woman.

Though the White woman offered no protest, the bus driver ordered the two Black students to move to the back of the bus. They refused, but offered to get off the bus if the driver refunded their dimes. The driver refused and instead drove to a nearby service station and called police. Within days, the Tallahassee Civil Rights Movement had begun.

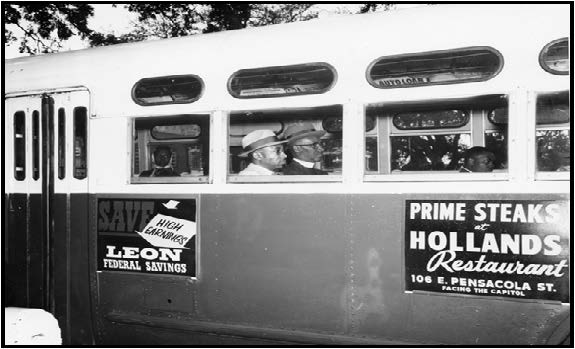

After the arrest of Patterson and Jakes, FAMU students announced a boycott of city buses, urging Black residents – the bus company’s main customers – not to ride the buses. Leadership of the boycott soon passed to the Inter-Civic Council, an organization of Black pastors, business owners and workers, led by the Rev. C .K. Steele.

The boycott proved successful. By July, the buses had quit running because of a lack of customers. By the following summer, the bus system was fully integrated with Black drivers having been hired and Blacks allowed to sit anywhere on a bus.

On Thursday, May 26, Tallahassee will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the 1956 bus boycott. Most of those who participated in the history changing, seven months long event are dead, including Patterson and Jakes.

But their courage and impact will live on.

“We saw people from all walks of life come together on this issue. Nobody said it shouldn’t or couldn’t be done,” said Henry Steele, son of Tallahassee civil rights leader C.K. Steele. “It was just so good to see the solidarity of everyone. I think the boycott will always be a major, major thing that will always come up when civil rights are talked about in Tallahassee.”

Tallahassee’s bus boycott was the third in the nation. Baton Rouge staged the first in 1953; Montgomery staged the most famous in 1955. Other bus boycotts followed in Atlanta, Miami, Tampa and South Carolina, as Black citizens protested policies that forbid integrated seating on public buses.

The boycotts set the stage for what became a constant series of 1960s demonstrations, protests and Freedom Rides that changed American race relations. The protests yielded the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968. They accelerated the desegregation of public schools and universities, first ordered by the Supreme Court in 1954.

They would lead, unfortunately, to the killing of civil rights leaders, such as Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King Jr.

But they would be the catalyst for creating a nation that today, while not fully free of racism and prejudice, is more open to all. They were the catalyst in providing equal economic, political and social opportunity for African Americans – and leading to the nation’s first Black president.

And Tallahassee played a major role.

The role came with a price.

In September 1956, 21 Tallahassee Black residents were arrested and convicted of illegally operating car pools, so that Black workers could get to their jobs without using the buses. The 21 men and women were fined $500 each and sentenced to 60 days in jail.

In January 1957, two Black FAMU students and one White FSU student were arrested for violating an assigned seating program crafted to end the boycott but maintain segregated seating. The three men were fined $500 and sentenced to 60 days in jail.

The boycott brought violence and vandalism. Crosses were burned at the homes of Patterson and Jakes and in front of Steele’s church, Bethel Baptist. Rocks were hurled through the windows of Steele’s home. Gunshots blew out the windows of a Black-owned grocery store. An attempt by Steele and other pastors to integrate the buses was canceled when 200 White youths armed with bats and rocks showed up.

But, the boycott changed attitudes. Several White citizens helped start a bi-racial committee to advance integration. Gov. LeRoy Collins, a Tallahassee native, began taking his first steps toward being the first Florida governor to support integration. A Black pastor, K.S. Dupont, became the first Black to run for the city commission since Reconstruction – and though he lost 6,804 votes to 2,405 votes, he received votes from 87 White people.

The boycott cracked open the door of Tallahassee’s Jim Crow racism and paved the way for Tallahassee civil rights protests. In 1960, FAMU students picketed all-White lunch counters. In 1963, FAMU and FSU students picketed local theaters over their segregated seating policies. Throughout the 1960s, local schools were slowly integrated, highlighted by the enrollment of three Black students at Leon High in 1963.

Today, Blacks and Whites sit anywhere they wish on the city owned StarMetro buses and 94 of StarMetro’s 107 bus drivers are Black. Tallahassee has had Black mayors, Black city managers, Black city chiefs of police and dozens more positions filled by Blacks.

“The boycott is the issue I credit for the contemporary civil rights movement beginning,” Henry Steele said. “It sort of pulled the nation into focus on the race issue and that something had to be done in more of a unified way. The bus boycotts were the issue everyone watched.

“They were a call to order.”

Gerald Ensley is a retired columnist for the Tallahassee Democrat newspaper. He can be contacted at geraldensley21f@gmail.