Symposium tackles minority health and wellness

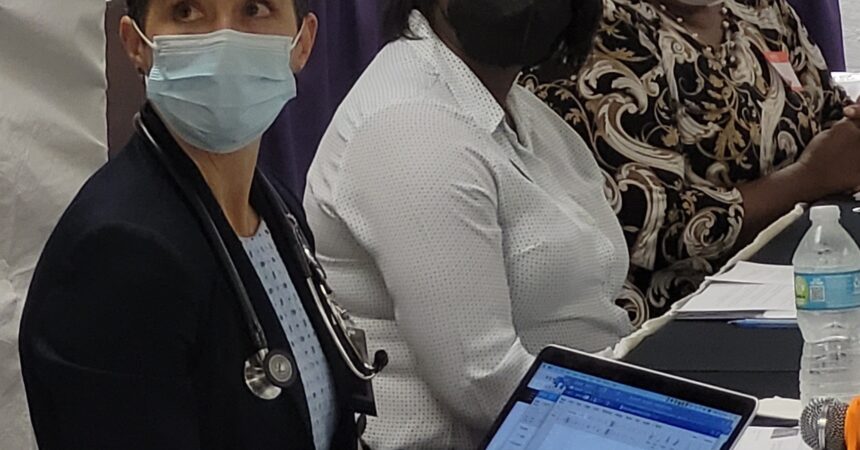

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

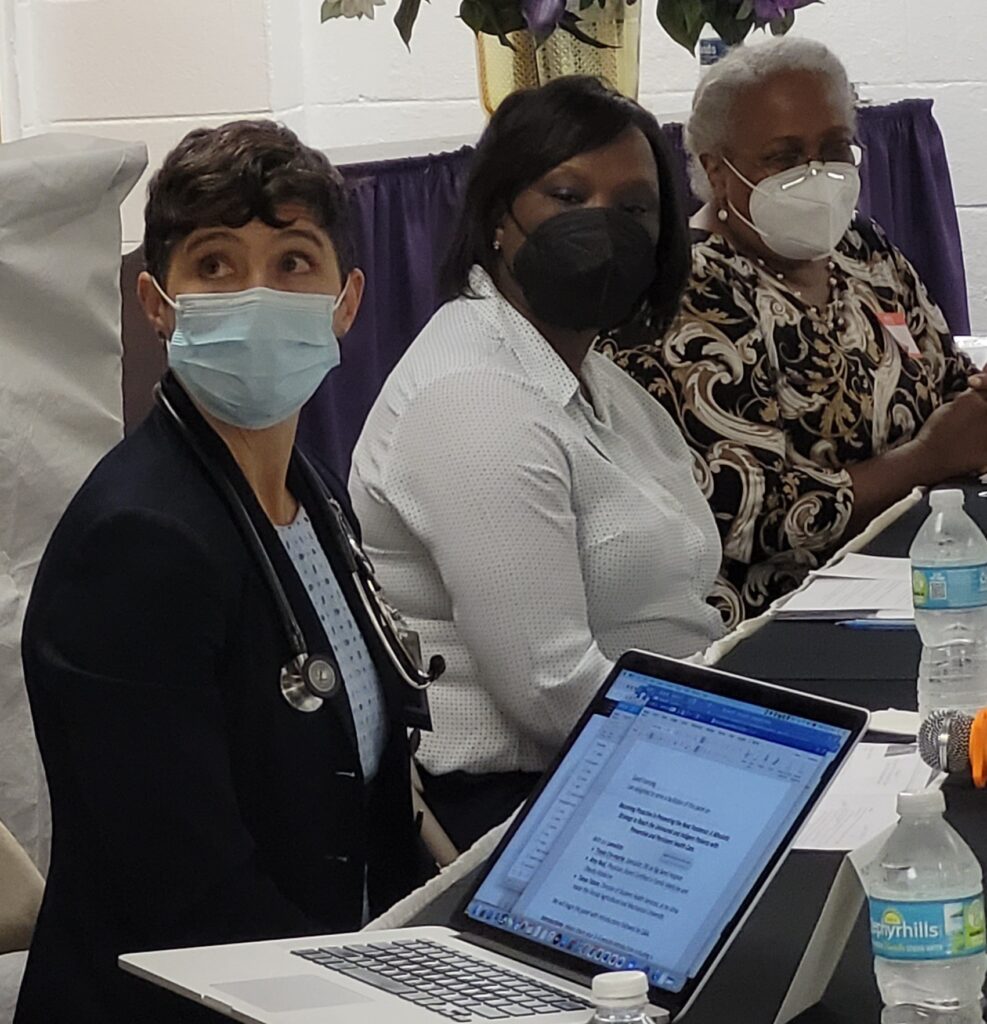

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

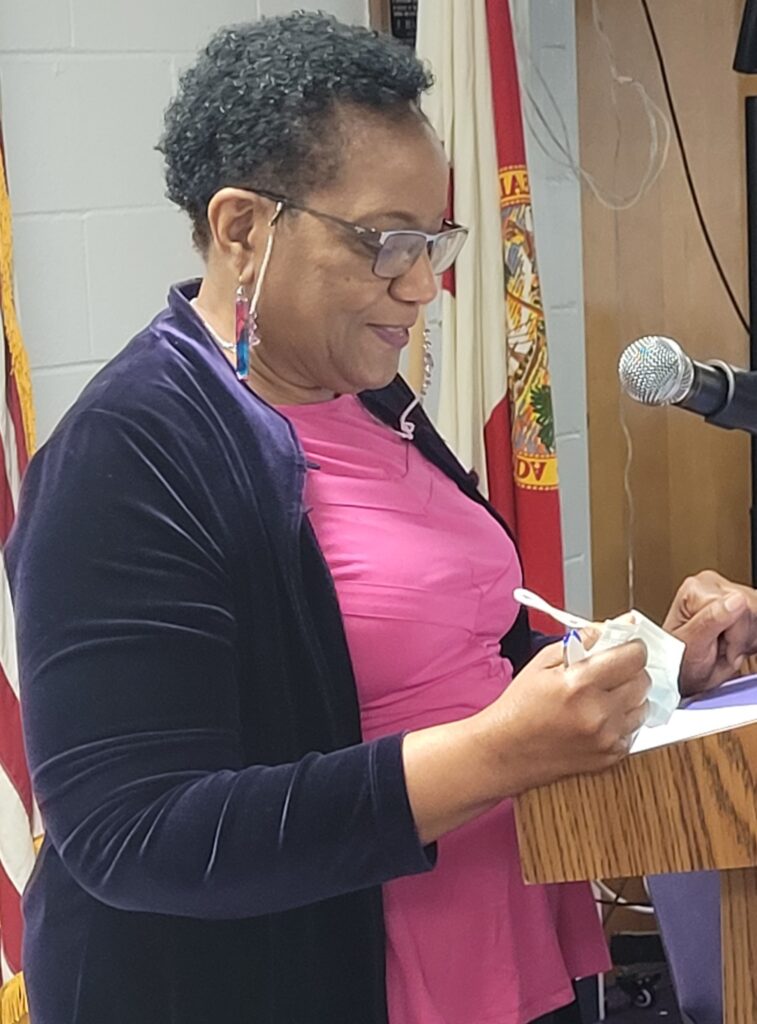

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook Staff Writer

Professionals from several disciplines in healthcare recently put the spotlight on disparities that were exposed by COVID-19 in minority communities, where several iniquities continue to exist.

While focusing on ways to deliver better healthcare, the group tackled three specific issues, each discussion led by a facilitator and a panel of experts. The discussion was inspired by disparities witnessed especially in rural communities by Dr. Claudette Harrell, project manager for the Bethel Mobile Medical Unit at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church, and others.

The topics covered healing marginalized communities, treating mental illness, and ways to become proactive in preventing the next pandemic. However, the challenge that many of the panelists’ experience has been in efforts to establish physician-patient relationships.

“When we go into a community, we talk to the voices of the community,” said Harrell. “We don’t go in there and try to usurp the authority of people within that community. We ask them ‘what is it you need for your quality of life to be better.’ ”

Throughout the symposium, speakers touched on how racial disparities in healthcare may have been exacerbated during the pandemic. That, said Harrell is one reason that she and her volunteer corps seek a holistic approach by turning to resources available through churches, Leon County Health Department or FSU, FAMU and TCC.

While most of the speakers focused on the overall health of minorities, Dr. Jay Reeve, president/CEO of Apalachee Center, took time to center his comments on mental health. Dispelling myths and finding ways to avoid labeling an individual as being a specific mental illness is an everyday challenge, he said.

Reeve used his personal example of being diagnosed with hypertension, pointing out that the condition isn’t his identity. That being the case, he noted that people with mental health disorders shouldn’t be identified as being what they are diagnosed with.

A mental health condition “doesn’t define people,” he said, expressing optimism that change will come.

“I think the more we meet like this, the more we talk about it the better it is; the better it gets,” Reeve said. “I think those of us who work in the mental health field has an absolute morale responsibility to be out front talking about these conditions. We have to be.”

Conversations in the area of medication also are essential, said Dr. Johnnie Early, Dean of FAMU College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science Institute of Public Health. One important way for a pharmacist to establish a relationship with patients is to ask, “What do you know about the medication that you were given?”

Older individuals who are prescribed medication should be especially cognizant about managing their prescriptions, he said.

“If you live beyond 50 that means you’re going to have medication in your life,” Early said. “The daily use of those medications means you’re going to have a longer, and certainly a healthier life.”

Since the onset of the pandemic, studies by Healthypeople.gov have found that the top five health disparities are race and ethnicity, gender, sexual identity and orientation, disability status or special health-care needs and geographic location whether its rural or urban.

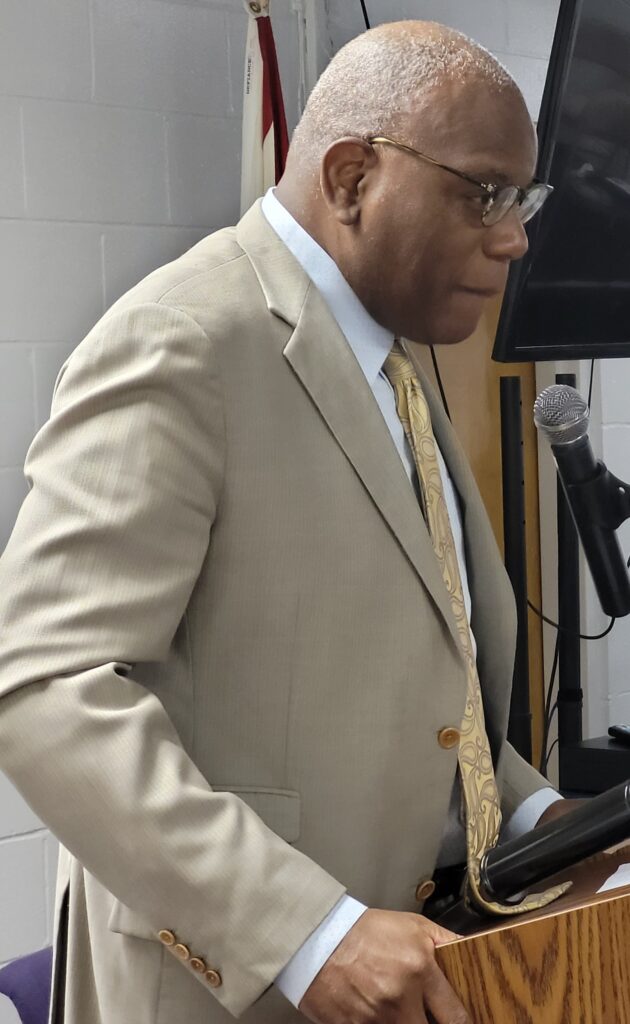

“As we move beyond COVID-19, we must continue to work diligently to close the healthcare disparities in marginalized communities,” said Rev. RB Holmes, pastor at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church who moderated the discussion. “We are elated in forging an historic and transformational partnership with Big Bend Hospice/Transitions Supportive Care. This unique partnership will enable us to bring comprehensive health care services to rural and other communities that have not been receiving quality healthcare at a consistent level.”

COVID-19 “was a big eye-opener for everybody,” said Amy Neal, who practices family medicine at Capital Health Plan. Improving healthcare in communities with flagrant disparities could require making change in times that services might be available, she said.

She added that individuals who work multiple jobs or even one often can’t skip work between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. Making such a choice is especially difficult for individuals who are providing for their families, said Sabrina Dickey, an associate professor in the FSU College of Nursing.

“Each individual has their own needs and what is going to be the motivator for them,” Dickey said. “With that, it might be this person needs to figure out which bill is going to get paid first, how they’re going to get food for their children; how they’re going to satisfy something they need.

“If you’re working at a job where if you don’t show up to work you don’t get paid; what do you think that decision is going to come down to.”

Having weekend clinic hours and mobile units could make a big difference, she said.

“That’s what we need; being able to have it right there at their fingertips and making it as easy as possible.”

But making healthcare services more available in underserved communities will take time to establish necessary relationships, said Dr. Lenny Marshall, director of diversity, equity and inclusion at Big Bend Hospice.

He called the symposium an essential event with meaningful discussions, but reminded the group “the steps to healing require the person who wants to be healed to take action.”