Robinson: Black colleges will have long existence

More than 1,000 people turned out for last Friday night’s screening of “Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities.”

Photo by Kanya Stewart

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook staff writer

Stanley Nelson’s documentary “Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities” answered a lot of questions about the genesis of Black colleges.

The 90-minute film is compelling from beginning to end, as it showed the struggles of Blacks in their fight for an education. As much as it clarified questions about the educating of Blacks from slavery to now, it ended with a student expressing concerns about the future of HBCUs.

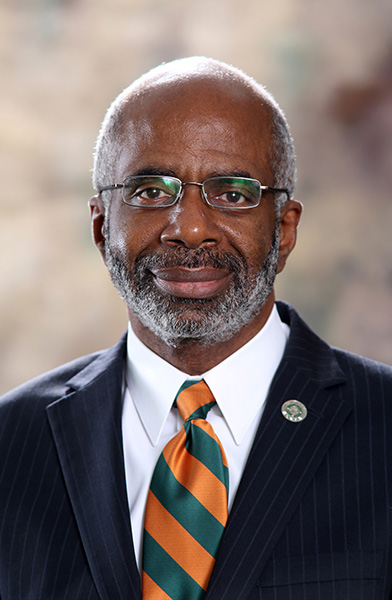

FAMU President Larry Robinson was profound when he responded during a question and answer session at the end of the screening at Lee Hall this past Friday night, saying that Black colleges will continue to exist. Robinson and other members of the panel spoke to an audience of more than 1,000.

“I think the day that we eliminate social injustice, economic disparities, health and medical disparities; the day we cure all those things HBCUs are no longer relevant,” Robinson said. “It looks like we are going to be in business for a very long time.”

There also was a consensus among the panelists that the HBCU culture has a lot to do with their existence.

Reginald Ellis, now a history professor at FAMU, named several of the university’s greats who influenced him when he went to FAMU as a teenager. At the time he discovered a culture where staffers on campus care about the wellbeing of students.

“I can’t forget that so that when my baby gets older he will start to hear about Florida A&M University,” he said. “The reason that his dad has a PhD today is because individuals took time out to mentor me when they didn’t have to. They saw something in me when I didn’t see anything in myself. It starts with us having the conversation at home and letting our children know that if my education was good enough it would be better for you.”

Ellis’ perspective was seen on the screen when FAMU students were featured. Both Jessika Ward and Calvin Long talked about the family atmosphere at FAMU.

The survival of Black colleges was one of the topics that Nelson gave extensive time in the film. In particular it highlighted Morris Brown College and its demise. That, in part, led to the question that prompted Robinson’s response.

The survival of HBCUs will, however, depend on Blacks supporting their alma maters in every way possible, Robinson said. Making sure that happens is an ongoing campaign for FAMU, he said.

“If you look at the most successful institutions out there, they get there in a large part by what they do to support themselves,” he said. “That’s not just about writing a check; it’s about political activism at the local level, the state level and the federal level.

“We have to make the powers that be in Washington, D.C., understand the value of what we bring. We have to make sure we get our fair share at the state level. We fight that battle every single day. We need all of us to engage in that battle because we think that in the end the value that FAMU offers the state of Florida is worth investing in.”

PBS will air the film nationally on Feb. 19. The viewing in Tallahassee was a partnership between WFSU Public Media, Firelight Films and FAMU.

Nelson also accounted for confrontations not well-known, such as the fatal shooting of Southern University students Denver Smith and Leonard Brown during a protest in the 1970s. Many more lives were lost over the education of Blacks during the past 130 years, amounting to at least 20,000, according to one historian in the film.

Philosophical differences between W.E.B Du Bois and Booker T Washington, who founded Tuskegee Institute, were concisely illustrated. For many in the audience it was the first time that they had such a detailed view of the conflicting philosophies: Washington with the backing of Whites advocated for vocational training, while Du Bois pushed for liberal arts curriculums.

Nelson delved into the film in the same deliberate manner he did when he directed other documentaries such as “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords” in 1999, “Murder of Emmitt Till” in 2003 and “Black Panthers” in 2015.

“We felt it was very important to showcase the film to students on HBCU campuses because this is a vital part of our African-American and American history,” Nelson said. “Many students and even alumni are not aware of the deep history of how and why HBCUs were created and the foundation for success they provided for African Americans.”

Nelson called on the expertise of HBCU historians throughout the film to tell the story. Intertwined in telling the legacy of Black colleges, were instances of the civil rights struggle.

“This is one of those stories that’s right in front of us,” said writer Marcia Smith. “But we don’t see it.”