Renaming a Southside street

Gamble’s name coming down, Robert and

Trudie Perkins’ going up

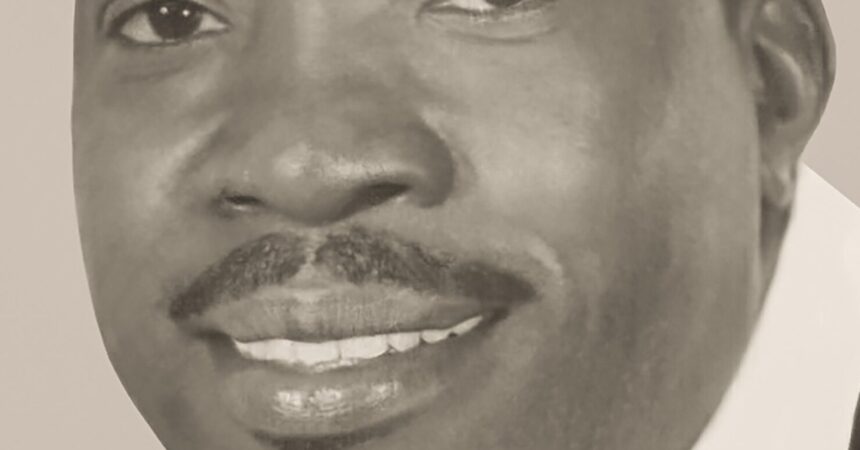

Photos submitted

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook staff writer

Activism by Robert and Trudie Perkins were everywhere around Tallahassee’s Black community, as discrete as it was kept.

Now more than 50 years after the couple’s action brought quality-of-life changes for Blacks, their names will be placed permanently on a roadway that runs through FAMU’s campus. Gamble Street, named for a former slave owner, will become the Robert and Trudie Way this fall.

The planned date of Sept. 10 would have been their 75th wedding anniversary. They become the first couple to have their names on a street sign.

Up until recently when the Leon County Commission voted to rename the street that stretches from FAMU Way to Martin Luther King Boulevard, little was known about Maj. Robert Gamble’s ties to slavery. The push for the name changed was led by Delaitre Hollinger and Jacqueline Perkins, daughter of Robert and Trudie.

Since the commission’s action she’s been feeling “a wide range of emotions,” said Jacqueline Perkins. “I’m proud of them and the work they did. But if my mother and father were alive today they would say this was not necessary and continue doing what they were doing.”

Hollinger, a Tallahassee historian who is the Executive Director of the National Association for the Preservation of African-American History and Culture, first learned about the Perkins’ activism when their son, Reggie, brought it to his attention. Months of researching led to discoveries about what the couple did for Blacks, starting in the 1950’s.

The couple, who occasionally worked with more prominent civil rights activist like Rev. C.K. Steele, unequivocally belongs in the unsung heroes category, Hollinger said.

“What is so significant about this is that Robert and Trudie Perkins were both graduates from Florida A&M University,” he said. “They went on to change the very face of this city. Seeing these individuals honored as opposed to a slave owner who oppressed Black people, it is something that our entire university community can be proud of.”

He called the Gamble name a stain that runs through FAMU campus that the change will erase.

“It should inspire the thousands of students who would be returning to Tallahassee this fall,” he said.

The Perkins constantly challenged City government on many fronts. When Robert Perkins questioned the city’s hiring practices for administrative jobs in 1975, federal judge Winston Arnow agreed with Perkins and mandated that the city hire Black people at a ratio of 23.7 percent, the ratio of Blacks who lived in Tallahassee at the time.

It was Perkins’ action in the early 1950’s that led to the city creating the Gaither Recreation and Parks for Negros in 1954. That was the city’s response to Perkins’ insistence on taking Black children from Bond to predominantly White recreation facilities.

Perkins even went as far as calling for the resignation of Gov. Reubin Askew for not appointing Black circuit judges. Not long after Joseph Hatchett became the first Black circuit judge.

Trudie Perkins, one of the first Black nurses to work at TMH, was very active on the labor front. She and coworker Lizzy Smith were involved in a movement to bring about better working conditions and pay for Black nurses.

It cost them their jobs.

Her parents, Jacqueline Perkins said, were “people who stood up (and) were positive and persistent.”

Perkins, who was a math and physics instructor at FAMU, left his job after being asked to sign a loyalty form, which would have been giving consent to segregation practices. Later he also lost his job at FSU where he was the first Black director of the computer center.

But by then he and his wife had a convenience store on the corner of Wahnish Way and Osceola Street. She ran a hair salon on the property, which also was the only Black-owned gas station with three pumps.

One of the first steps that Perkins and Hollinger took to have Gamble’s name removed was to approach the city through Commissioner Dianne Williams-Cox. She initially sought the name change for a portion of the street, omitting the sectioned owned by FAMU.

However, the university wrote a letter of support, clearing the way for the name-changing process to move forward.

Williams-Cox said she is especially pleased that the name of Gamble, who owned a sugar plantation in Ellenton, near Bradenton, will be removed.

“It was a stigma for those who knew, but I’m proud that my beloved FAMU will not have a slave owner’s name running through it,” Williams-Cox said. “We know that there are others in our city. I don’t know where that is going to go, but right now we are glad to have this one undone and put the names of folks who have helped our city and our community.”

Robert Perkins died in 1994. His wife Trudie died 17 years later. While they might have been unsung, despite the work they’ve done, their legacy will live on as activists who made profound changes for Blacks.

“It is a testament to what two people or a single individual can do when they put their mind to something and go after something vigorously and unrelentingly,” said Hollenger. “They were responsible for giving so much to the FAMU community and the Bond community.”