Museum memorializing Black lynching victims opens in Montgomery, Alabama

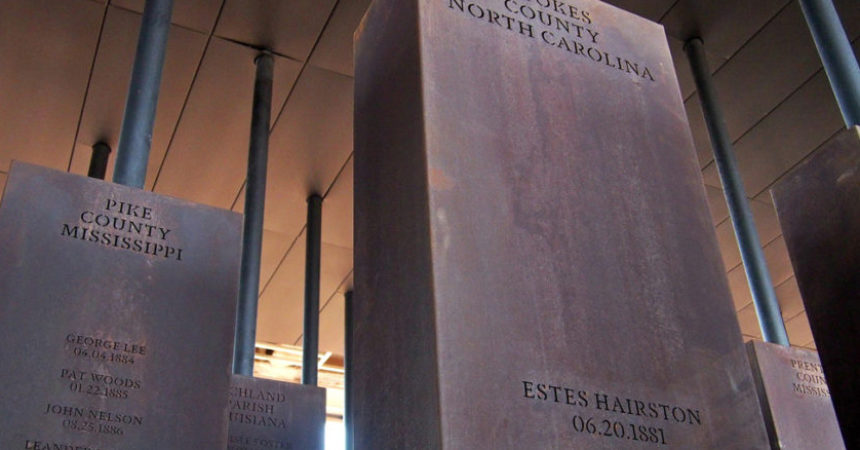

The names of lynching victims and the counties where they were murdered.

Photos courtesy of Trice Edney News Wire

By Frederick H. Lowe

Trice Edney News Wire

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum has opened to teach American history never published in textbooks.

The museum is a memorial to the documented 4,400 African-Americans murdered in lynchings, which included beatings, drownings and being burned at the stake by Whites between 1877 and 1950 in 12 Southern States, including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

The names are engraved on duplicate sets of columns, two for each county where a lynching was documented. Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) initially reported that 3,959 African-Americans were victims of lynchings in the 12 states but added to the number as more victims became known.

The lynchings forced Blacks to flee in terror from the South to the North. “Black people living in Oakland, California, Chicago, and New York are refugees from terror. They fled the South to escape lynching,” said Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, which had the museum constructed to pull the wraps off an untold story of America’s history. The story will make some Blacks as well as Whites uncomfortable and even angry.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama.

Historically, however, lynchings entertained some Whites. Some made a day of it, attending with picnic baskets.

The museum, which is located in Montgomery. Alabama, the state’s capital and one-time seat of the Confederacy, was founded by The Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit advocacy organization based in Montgomery. EJI published “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.”

Since the report’s release, EJI has supplemented its original research by documenting lynchings in states outside the Deep South. Lynchings, for example, occurred in Minnesota, Indiana, Illinois, West Virginia and Nebraska.

On June 15, 1920, a mob dragged Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie, employees of the John Robinson Circus, from their jail cells and lynched them for allegedly raping Irene Tusken, a 19-year-old, although Dr. David Graham’s examination of Tusken found no evidence of sexual assault.

That information did not prevent newspapers from publishing numerous stories about the alleged rape. The story about the lynchings is told in the 1979 book “The Lynchings in Duluth,” by Michael Fedo. A photo of the three men who had been lynched was made into postcards at the time and shown throughout Duluth.

Bob Dylan’s song “Desolation Row” recalls the lynching. Dylan was born in Duluth but grew up in Hibbing, Minnesota.

Future Academy Award winning actor Henry Fonda witnessed the 1919 lynching of Will Brown in his hometown of Omaha, Nebraska, when he was a boy. Fonda was born in 1905.

White terrorists burned Brown, a 40-year-old meat-packing worker, at the stake for allegedly raping a White woman.

“It was the most horrendous sight I’d ever seen… My hands were wet and there were tears in my eyes. All I could think of was that young Black man dangling at the end of a rope,” Fonda said.

EJI also released a study about Black military veterans targeted for lynching. The report’s title is “Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans.” It builds on EJI’s 2015 report, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.”

More than 90 percent of terrorist lynching victims were Black men, and some of the victims were boys as young as 12 and 13, Stevenson told NorthStar News Today.com and BlackmansStreet.Today in 2015.

The study noted that at least 800 more African-Americans were murdered in lynchings than had been previously reported. The report focuses on racial terrorist lynching, which Whites, including the police, elected officials, ordinary citizens and federal bureaucrats participated in the murders or condoned them to enforce Jim Crow laws and racial segregation.

Lynching victims were murdered without being accused of any crime; they were killed for minor social transgressions, including bumping a White person, wearing their military uniforms after World War I and not using the appropriate title to address a White person.

For example, General Lee, a Black man, was lynched in 1904 by a White mob in Reevesville, Ga., for knocking on the door of a White woman’s home. In 1919, a White mob in Blakely, Ga., lynched William Little, a soldier returning from World War I, for refusing to take off his uniform. And in 1916, White men lynched Jeff Brown in Cedarbluff, Miss., for accidentally bumping into a White girl as he ran to catch a train.

Thousands of volunteers for EJI have collected soil from over 300 lynching sites as part of the organization’s Community Remembrance Project. The jars of soil are exhibited at EJI. Each jar bears the name of a man, woman, or child lynched in America, as well as the date and location of the lynching.

Work on the memorial began in 2010 when EJI staff began investigating thousands of racial-terror lynchings in the South, many of which had never been documented. This research ultimately produced the first report.

There is an admission fee and fees to attend other museum events. During the museum’s opening week, speakers included Michelle Alexander, author of the book “The New Jim Crow,” former Vice President Al Gore, U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D. NJ), and Ray Hinton, who spent nearly 30 years on Alabama’s death row for a crime he did not commit.

The museum also hosted a concert featuring Common and Usher.