Martinsville Seven pardoned

Photo by Regina H. Boone/Richmond Free Press

Special to TriceEdneyWire.com

From the Richmond Free Press

It took 70 years, but the Martinsville Seven have finally been pardoned.

Gov. Ralph S. Northam granted posthumous pardons on Aug. 31 to the seven Black men who were executed in 1951 for the rape of a 32-year-old White woman. All of them were tried by all-White male juries. Four of the men were executed in Virginia’s electric chair on Feb. 2, 1951. Three days later, the remaining three also were elect0rocuted.

It was the largest group of people executed for a single-victim crime in Virginia’s history. The case attracted pleas for mercy from around the world and in recent years has been denounced as an example of racial disparity in the use of the death penalty.

The governor announced the pardons after meeting with about a dozen descendants of the men and their advocates. Cries and sobs could be heard from some of the descendants after his pardon announcement.

“Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Lord,” James Walter Grayson of Baltimore, the 74-year-old son of Francis DeSales Grayson, sobbed when Northam told family members during a meeting that he had granted the pardons.

Grayson said he was 4 when his father was executed.

“It means so much to me,” he said of the pardon.

“I remember the very day the police came to the door. He embraced each of us and said, ‘I will be back.’ They took him away, but he never came back.”

The pardon was issued on what would have been Francis DeSales Grayson’s 108th birthday.

“History was made today,” Grayson said. “I knew that God would move today, and He did.”

Rudolph McCollum Jr., a former Richmond mayor who is the great-nephew of Francis DeSales Grayson and the nephew of another one of the executed men, Booker T. Millner, told Northam the executions represent “a wound that continues to mar Virginia’s history and the efforts to move beyond its dubious past.”

He, too, wept when Northam announced he would pardon the men.

In addition to Grayson, who was 37 at the time, and Millner, who was 19, the other members of the Martinsville Seven who were pardoned are Frank Hairston Jr., 18; Howard Lee Hairston, 18; James Luther Hairston, 20; Joe Henry Hampton, 19; and John Clabon Taylor, 21.

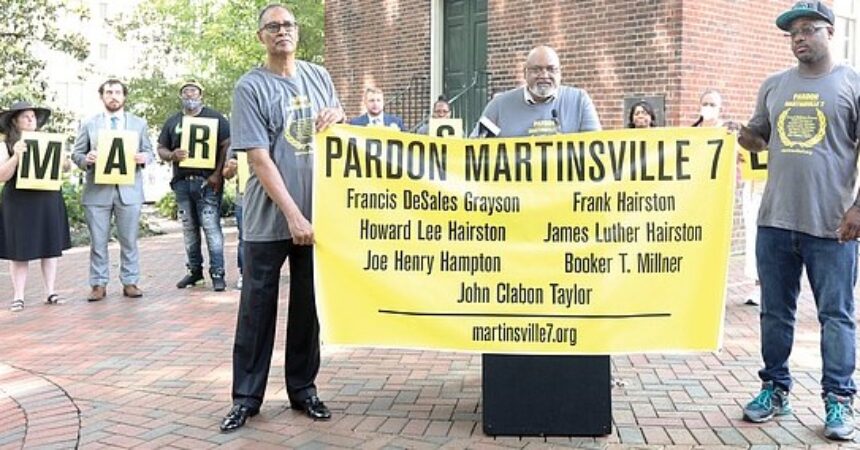

A rally at the Bell Tower on Capital Square that was intended to be a plea for their pardon turned into a celebration following the governor’s announcement.

“This case is symbolic of Jim Crow, racism at its basest and injustice in the criminal justice system,” McCollum told the small crowd of family members and supporters.

He credited among others law students at the College of William & Mary for preparing the legal documents to support the pardon request.

The Martinsville Seven, as the men became known, were all convicted of raping Ruby Stroud Floyd, a White woman who had gone to a predominantly Black neighborhood in Martinsville on Jan. 8, 1949, to collect money for clothes she had sold.

At the time, rape was a capital offense. But the death penalty for rape was applied almost exclusively to Black people.

From 1908 — when Virginia began using the electric chair — to 1951, state records show that all 45 people executed for rape were Black, Northam said.

The pardons do not address the guilt or innocence of the men, but Northam said the pardons are an acknowledgement that they did not receive due process and received a “racially-biased death sentence not similarly applied to White defendants.”

“These men were executed because they were Black, and that’s not right,” he said. “Their punishment did not fit the crime. They should not have been executed.”

All seven men were convicted and sentenced to death within eight days. Northam said some of the defendants were impaired at the time of their arrests or unable to read confessions they signed. He said none of the men had attorneys present while they were interrogated.

Before their executions, protesters picketed at the White House, and the governor’s office received letters from around the world asking for mercy.

In December, advocates and descendants of the men asked Northam to issue posthumous pardons. Their petition does not argue that the men were innocent, but says their trials were unfair and the punishment was extreme and unjust.

“The Martinsville Seven were not given adequate due process ‘simply for being Black,’ they were sentenced to death for a crime that a White person would not have been executed for ‘simply for being Black,’ and they were killed, by the Commonwealth, ‘simply for being Black,’ ” the advocates wrote in their letter to the governor.

Dr. Eric W. Rise, an associate professor at the University of Delaware who wrote a 1995 book on the case: “The Martinsville Seven: Race, Rape, and Capital Punishment,” said Floyd told police she was raped by a large group of Black men and testified at all six trials. Two of the men were tried together.

All seven men signed statements admitting they were present during the attack, but they had no access to their parents or attorneys at the time, Dr. Rise said.

“The validity of the confessions were one of the things their defense attorneys brought up at the trials,” Dr. Rise said.

Four of the men testified in their own defense. Dr. Rise said two men said they had consensual sex with her, one man denied any involvement, and another man said he was so intoxicated he could not remember what happened.

Northam now has granted a total of 604 pardons since taking office in 2018, more than the previous nine governors combined, his administration announced.

“This is about righting wrongs,” Northam said. “We all deserve a criminal justice system that is fair, equal, and gets it right — no matter who you are or what you look like,” he said.

In March, Northam, a Democrat, signed legislation passed by the Democrat-controlled legislature abolishing the state’s death penalty. It was a dramatic shift for Virginia, a state that had the second-highest number of executions in the United States.

The case of the Martinsville Seven was cited during the legislative debate as an example of the disproportionate use of the death penalty against people of color.