Humphries had the perfect plan to make corporations buy into educating Black students

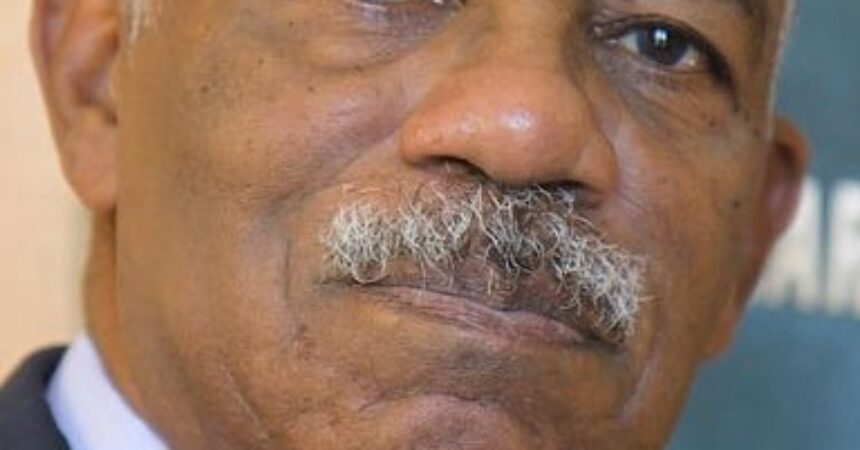

In 1985, Frederick S. Humphries was planning an attack on the soul of higher education in America. He believed this na-tion had promised African American students, that if they worked hard and earned good grades, merit would overcome racism. His development team produced a proposal called “Life Gets Better.” Humphries slid copies of the proposal targeted for Fortune 500 corporations into a briefcase and put on his traveling shoes.

He squeezed five corporations into a single day’s meeting, selling his proposal at full strength in the early morning hours and somehow got stronger as the day grew longer. Intellectually he was off the charts, whip smart with a photographic memory, and a distinguished scientist with a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh. But he was a born salesman who could have earned millions in the business world. And although higher education was his wheelhouse, he never lost a sale.

The proposal called for corporations to join the University’s Cluster Program with an annual $1,500 membership fee and support for the Life Gets Better Scholarship program covering the full cost of a college education. When he retired the Cluster had grown to more than 100 Fortune 500 Corporations who contributed $3 to $4 million annually.

Alumni within the sound of Humphries’ voice received the same treatment. Telling Humphries how much you loved FAMU didn’t mean much unless it was backed up with cash and pledges. A fiery temper was in store for the University Relations team who did not have pledge forms on hand when Humphries was talking to alumni. The FAMU Foundation had an endowment of less than $6 million when Humphries become president. When he retired in 2001, the endowment was approaching $70 million. Today the endowment is $125 million.

Proving that FAMU’s majority African American faculty and student body could perform at an equal level with other institutions was not in his strike zone. He didn’t want to play for a tie. He wanted to win. Humphries envisioned FAMU as a Mecca that attracted the nation’s best and brightest African American faculty and students and an epicenter for innovations in higher education.

The late Joseph A Johnson was the Herbert Kayser Professor of Science and Engineering at City College of New York with nearly 100 peer review publications. He told Humphries he would come to FAMU if he could have the same size research laboratory and equipment he had at City College. Humphries made it happen.

When a student appeared on the cover of Parade Magazine for winning millions of dollars in scholarship funds, Humphries phoned her. She refused his offer but did agree to visit the campus. When Humphries hung up the phone he said, “I got her. After she visits the School of Business and Industry, I’m going to make her an offer. He did and she accepted. He spent countless hours on the telephone calling students. When one student said no, because she was going to Georgia Tech. Humphries asked her if the President of Georgia Tech had called her. She said no. And then said, “Dr. Humphries, I will see you in September.”

Enrollment soared to nearly 13,000. FAMU graduates with PhDs in engineering, environmental sciences, physics, pharmacy, education and MBAs in business were multiplying. Faculty research funds were at an all time high approaching nearly $50 million dollars. National and international recognition followed. In 1989, the Marching 100 was invited by the government of France to be the sole U.S. representative at its Bicentennial Celebration of the French Revolution. In 1997 The Time Magazine Review/Princeton Review named FAMU as its first College of the Year.

Outside the campus boundaries, on the streets of Tallahassee and beyond, White supremacy ideology loomed like dark clouds on a sunny day. Its leaders were so busy with racial chicanery, they didn’t see Humphries coming. Inside the campus, an educational enterprise was at work, creating a new world one graduation at a time.

Humphries’ Rattler spirit was born on a windswept day in 1952 in Bragg Stadium when he was a senior in high school in Apalachicola. He had driven over with a few friends to watch the Rattlers take on the North Carolina A&T Aggies. The Rattlers were behind at halftime 12-6. President George w. Gore, Jr. strode majestically to the field at halftime. His strong baritone voice said just a few words: My fellow FAM-Uans, do not be concerned about the outcome of the game. You must always remember, the Rattlers will strike! And strike and strike again.

Pandemonium ensued. The crowd went wild and Humphries joined in. Then he saw dust swirling through the air behind the east stands. And he saw something and heard a sound he would never forget. The Marching 100 had entered the field moving at 300 steps a minute.

Humphries was overwhelmed by the precision marching and complex formations, but nothing touched him like the gran-deur of that extraordinary sound. It caught a ride on the wind, reached into his heart and never let him go. FAMU won the game 19-12.

I am convinced that the last sound he heard was that of the Marching 100 performing his favorite song, “Total Praise,” and that extraordinary sound took him home.

Eddie Jackson is a retired FAMU vice president of University Relations who worked closely with Humphries.