How Obama is Addressing the Crisis Among Boys and Young Men of Color

Pool/Getty Images

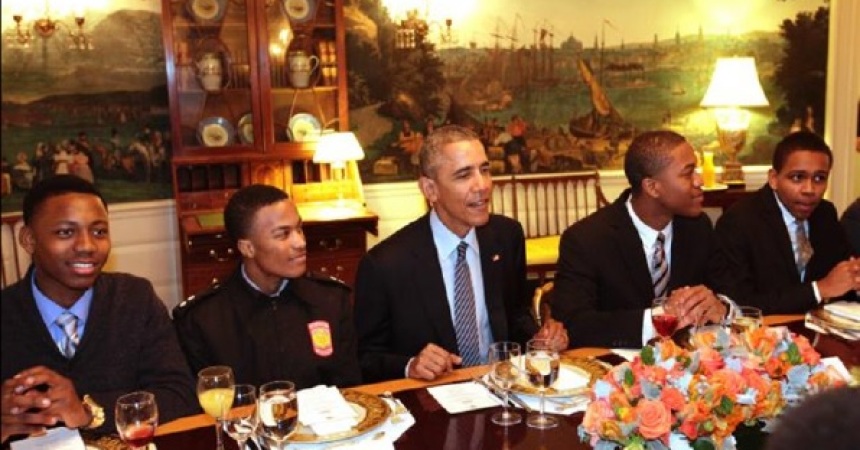

President Barack Obama has lunch with young participants in the My Brother’s Keeper initiative at the White House Feb. 27, 2015, in Washington, D.C. Chris Kleponis

Feb. 27, 2015, in Washington, D.C. Chris Kleponis

By Nigel Roberts

The Root

It was easy to mistake last week’s gathering at a New York City hotel for a religious meeting.

for a religious meeting.

One panelist, who proudly proclaimed his Baptist-preacher lineage, issued the rallying cry in his opening remarks: “God is good all the time.” But the roughly 200 people in attendance had gathered at the National Action Committee’s panel discussion in midtown Manhattan not to hear a sermon but to learn what they could do to save endangered young black men.

We’re familiar with the statistics. In 2013, only 14 percent of black boys demonstrated proficiency on the national fourth-grade reading assessment. The reality is that most of those who lag behind from that early stage will have few good options in life, and their life paths, all too often, will lead to incarceration.

Broderick Johnson, President Barack Obama’s representative at the discussion, part of NAN’s annual convention, was center stage. Johnson, who is Obama’s assistant and White House Cabinet secretary, also chairs the task force for the president’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, which launched in February 2014 and seeks to empower young men of color.

Johnson, who coordinates a broad coalition of federal agencies and private-sector partners, said that the president has long been concerned—since his days as a community organizer—about the issues that hinder young men of color.

“In the aftermath of the Trayvon Martin shooting, the president felt a sense of need to do something big,” Johnson told The Root. “What also motivated him to launch MBK was his unique position [as president] and ability to bring like-minded people together around his passion for this issue.”

An early benchmark of success, Johnson said, is the positive nationwide response. Nearly 200 cities (including the nation’s largest urban centers) and 17 tribal nations have accepted the MBK Community Challenge.

Last week Philadelphia unveiled what Johnson described as one of the more “extensive” and “impressive” MBK action plans. The private sector has also been a key partner in the president’s initiative. Foundations and corporations contributed nearly $200 million at the launch of MBK.

When asked about the Republicans’ response to MBK, Johnson said that they’ve been largely supportive. He explained that MBK is not “a big new federal program ,” so he hasn’t had to do that type of outreach. Most of his interaction with them has been at the state and community levels. He pointed to Indianapolis’ Republican Mayor Greg Ballard as an example. The city launched “a very aggressive MBK program,” Johnson said.

,” so he hasn’t had to do that type of outreach. Most of his interaction with them has been at the state and community levels. He pointed to Indianapolis’ Republican Mayor Greg Ballard as an example. The city launched “a very aggressive MBK program,” Johnson said.

But will these efforts continue after President Obama leaves office? Johnson gave a resounding, “Absolutely.” He said that the private sector is committed to the long-term success of MBK, and a foundation is in place to help coordinate the community effort.

after President Obama leaves office? Johnson gave a resounding, “Absolutely.” He said that the private sector is committed to the long-term success of MBK, and a foundation is in place to help coordinate the community effort.

Indeed, Johnson made it clear that MBK will be one of the president’s important legacies. He believes that future generations will say the president used his passion and office to improve the life outcomes for young men of color, who are the most challenged in our society.

“Most of all, people will say President Obama convinced the country, as no other president has done before, that the fate of these young men is linked to the fate and success of this nation,” Johnson said.