HOF induction solidifies Hubbard’s FAMU legacy

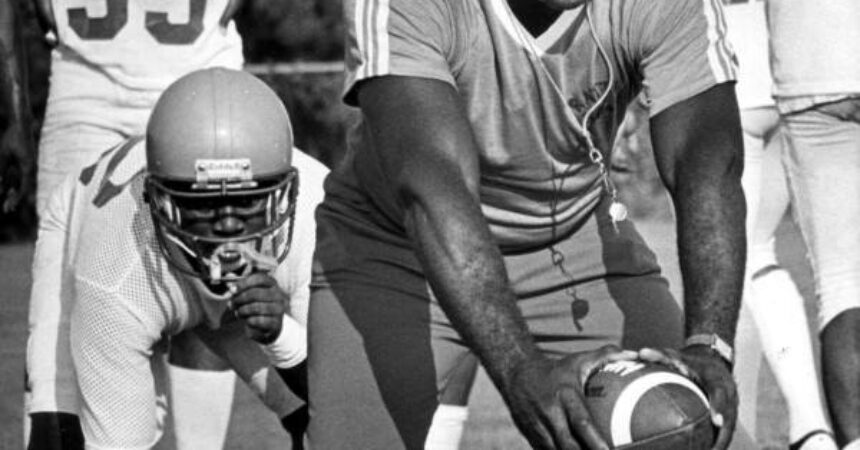

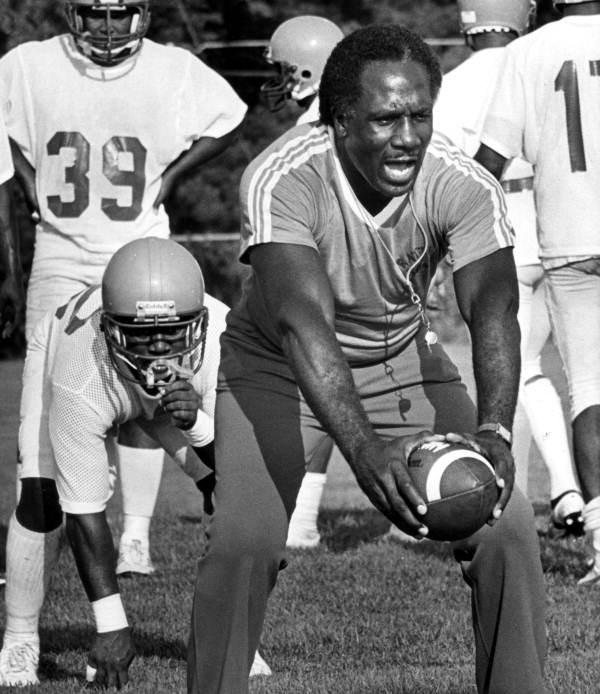

Photo special to the Outlook

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook staff writer

For several years after Rudy Hubbard left FAMU as head football coach, his name would surface around the time that the conversation began about who gets into the National Football Foundation’s Hall of Fame.

The media would clamor and Hubbard would be left wondering what happened. Folks who knew him never gave up believing that Hubbard’s time would come.

His legacy as former head football coach at FAMU was already established. Induction only seemed fitting. A few weeks ago, Hubbard got the call and the proof that he will be inducted in the Hall of Fame later this year.

While there is a sentiment that Hubbard can now begin to talk about a legacy as a hall of famer, he’d established the kind of credentials that made him worthy for the induction, which is considered the pinnacle for a college coach.

A lot of what Hubbard accomplished after he arrived at FAMU in 1974 as a young Black coach with fresh ideas is well documented although not entirely known by many in the new generation of Rattlers.

Making it into the Hall of Fame might be the claim that counts as legacy to some, but Hubbard had already achieved that.

Consider: Hubbard had an undefeated season. He won a Black College Football championship.

He led the Rattlers to a field goal win over the University of Miami. And, he will forever be the coach that led the first HBCU program to a national title for taking the I-AA championship.

Then there was a stretch between1976 and early in the 1978 season when FAMU had the longest winning streak in I-AA football at the time.

The induction is part of somewhat of a whirlwind that Hubbard is experiencing. This summer he will return to Columbus, Ohio, to be part of a city-wide fund-raising event that also recognized Buster Douglas for his upset of Mike Tyson.

Hubbard is also putting the finishing touches on a book that he hopes to release this summer. He simply refers to 2021 as his year.

“It seems like everything is just happening right now,” Hubbard said. ”It’s crazy but it’s a thing that I could see.”

The recognition is cool, but the long winning steak plus winning the I-AA title might arguably be among the accomplishments that make it difficult to deny the legacy that Hubbard has established.

“You will never see another Historically Black College win the I-AA national championship,” said Albert Chester, who was quarterback for the Rattlers for four seasons, starting in 1975. “You can hang your hat on that with Rudy Hubbard.”

When the news came a few weeks ago that the CFF has finally decided to put Hubbard in its HOF, he had a little bit of a hard time believing it. He let the package that enclosed confirmation of his induction sit around his home for a little while before opening it.

He wasn’t expecting such a package, Hubbard said.

It didn’t take long for word to get out that Hubbard has arrived at the place where great coaches are recognized. Reporters started calling and Hubbard spent a lot of time talking about his amazement.

“Each year my name goes on the ballot, then continues to roll over year after year,” he said in a prepared statement. “You start wondering if this will ever happen.”

He shouldn’t have been surprised. He’d planted the seed when he gave players like Chester and Clarence Hawkins leadership roles with the football team.

Hubbard spent a lot of time trying to make believers of the players that he inherited when he arrived from Ohio State, where he was a player and later became an assistant coach as the first Black to do so. He reminded them to do the little things right and trust his system, Hawkins recalled.

“There was evidence that we just couldn’t go out and do things the way that we thought we needed to do them,” Hawkins said. “We had to execute our assignments and do the little things well on every play.”

Essentially what Hubbard did was establish one of the best HBCU program. He had the talent to do it, too.

“We were fast,” said Hawkins, who was a running back. “We could run on both sides of the football. We had excellent speed.”

The confidence was so high that Hawkins suggested that they made swagger a thing.

“It wasn’t a matter of whether we were going to win,” Chester said. “It was how badly we were going to beat you. That’s how confident we were.”