Florida’s elections laws worrisome to congressional panel

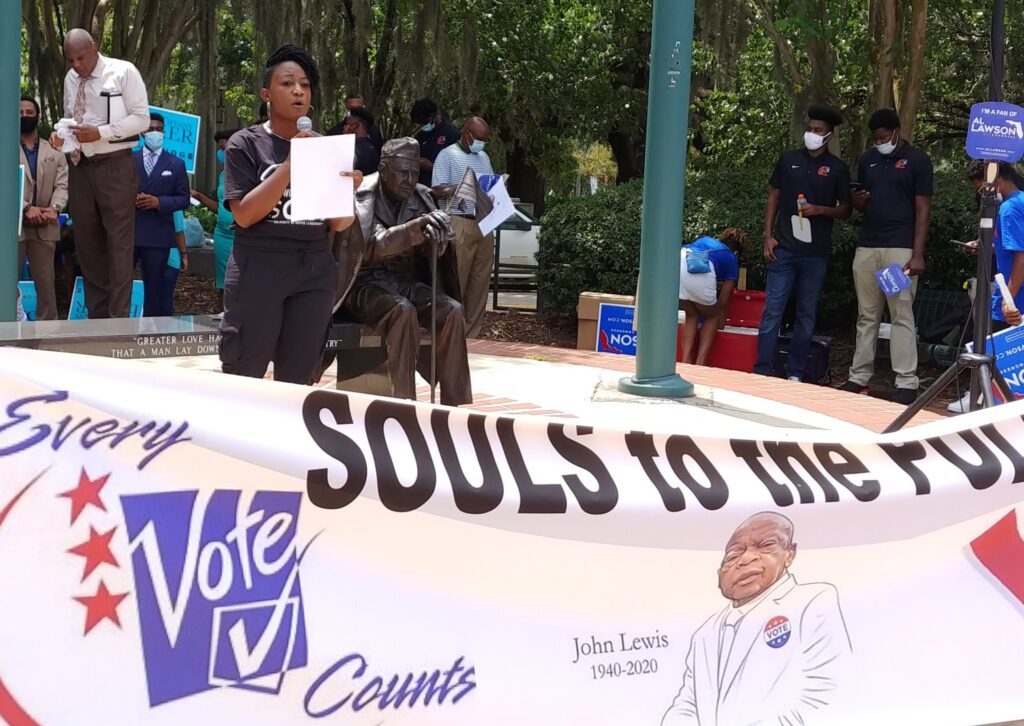

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

By Dara Kam

News Service of Florida

A congressional panel probing changes to elections laws across the country held a hearing in Tallahassee, illustrating a partisan divide over voting-related measures pushed in Republican-led states such as Florida.

The U.S. Committee on House Administration Subcommittee on Elections heard testimony last Wednesday from elections experts critical of voting restrictions passed by the Florida Legislature over the past two years.

The subcommittee also heard from Seminole County Supervisor of Elections Christopher Anderson, who was appointed by Gov. Ron DeSantis in 2019.

U.S. Rep. G. K. Butterfield, a North Carolina Democrat who chairs the subcommittee, expressed concern over a 2022 law — championed by DeSantis — that created an Office of Elections Crimes and Security in the Florida Department of State.

What critics call the “elections police” would be overseen by Secretary of State Cord Byrd, a conservative Republican appointed by DeSantis this month as the state’s top elections official.

The creation of the Office of Elections Crimes and Security came as Republicans throughout the country continue to feed a false narrative surrounding the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, in which Democrat Joe Biden defeated Republican Donald Trump.

Byrd, speaking to reporters at a conference of the state’s elections supervisors this week, refused to say whether Biden won the election but repeatedly maintained that Congress “certified” him as president.

The Office of Elections Crimes and Security would have the authority to independently launch probes into purported voting irregularities. The Legislature included it in an elections law that also calls for the appointment of Florida Department of Law Enforcement officers to investigate allegations of elections violations, with at least one officer in each region of the state.

Butterfield accused DeSantis, who is widely seen as a top contender for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, of “attempting to politicize a problem that doesn’t exist.” The chairman noted that Florida has seen few examples of voting fraud or wrongdoing.

“It is a waste of time and energy, and it sends the wrong message to the Floridians and to those wanting to vote,” Butterfield, a former judge, told reporters after last Wednesday’s meeting.

Florida prosecutors and local law-enforcement agencies “are very capable” of addressing election-related crimes, Butterfield said.

“But to create any elections police is unprecedented. I don’t know of any other state in the country that does that. And it tells me that the governor is simply trying to grab a headline,” he added.

The subcommittee decided to hold a hearing in Florida “because we had negative reports about legislation coming out of the state that affects the right to vote,” said Butterfield, whose panel held meetings this year in New Mexico and Texas.

But U.S. Rep. Brian Steil, a Wisconsin Republican who serves on the subcommittee and who attended last Wednesday’s meeting via video, blamed Democrats for eroding voters’ confidence in elections by criticizing what he called “election integrity” laws.

“What we’re actually seeing is laws being put in place that make it easy to vote and hard to cheat,” Steil said. “Florida has worked hard to strengthen their laws to ensure free, fair and secure elections. … It’s those on the left who are undermining our democracy by making false claims.”

Matletha Bennette, a senior staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Voting Rights Group, said the elections policing is “a terrifying reminder of this country’s history of using law enforcement to threaten and intimidate people from voting.”

Other speakers also expressed concern about the investigative unit.

“A lot of us are on guard how this entity can be used to challenge (election) results … maybe create momentum to overturn them,” said Brad Ashwell, Florida director of the group All Voting Is Local. “It’s clear that that’s no longer a far-out possibility.”

Gadsden County Commissioner Brenda Holt said members of her community, which is the state’s only predominantly Black county, also are wary of recent changes.

“The term election police is intimidating in itself, because the citizens don’t know if there are going to be officers at the polling place,” Holt said. “To do that during an election year is intimidating also.”

Since the 2020 presidential elections, the Republican-controlled Legislature also has passed measures that have made it harder for voters to cast ballots by mail, imposed new regulations on voter-registration groups and heightened sanctions or created new voting-related crimes.

After Florida voters approved a 2018 constitutional amendment aimed at restoring voting rights to felons who have served their time behind bars, the Legislature passed a law requiring felons to pay court fees and fines associated with their crimes before being able to vote.

As part of the once-a-decade redistricting process, state lawmakers recently approved a congressional map that would boost the number of GOP seats and revamp Congressional District 5, a district that stretches across North Florida from Jacksonville to east of Tallahassee. The seat is currently held by U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, who is a Black Democrat.

Lawson, who attended Wednesday’s meeting, called the slew of election-law changes in Florida “just ridiculous.”

Critics maintain that the repeated changes have a disparately negative impact on Black and Hispanic voters. Holt told the subcommittee that the changes are undermining Black voters’ confidence in the electoral process.

“These are things that are concerning. They cause hardship on people that already do not have money to do that,” Holt said. “What happened to just doing the right thing to help people? … Minorities do not trust these new laws.”

But Steil pressed Anderson about whether a “disconnect” with voters is creating problems for elections officials.

“Do you think it’s more challenging, due to the rhetoric on the left that they continue to beat the drum to tell people that it’s difficult to vote?” Steil asked.

“What I find is that the misinformation, it’s hard to pierce through the noise,” Anderson said.