Federal judge clears way for felons to vote

Opening the door for hundreds of thousands of convicted felons to be added to Florida’s voting rolls, a federal judge on Sunday struck down major parts of a state law requiring felons to pay court-ordered “legal financial obligations” to be eligible to vote.

U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle’s highly anticipated ruling also laid out a procedure for state elections officials to determine whether felons seeking to vote have outstanding legal financial obligations and are unable to pay court-ordered debts.

Hinkle’s decision came less than a month after an eight-day trial in the lawsuit, filed by voting- and civil-rights groups who alleged that linking voting rights and finances amounts to an unconstitutional “poll tax.”

The record “shows that the mine-run of felons affected by the pay-to-vote requirement are genuinely unable to pay,” Hinkle wrote in Sunday’s 125-page decision.

The law, approved by Republicans in a party-line vote last year, required felons who have completed their time behind bars to pay fees, fines, costs and restitution affiliated with their convictions to be eligible to cast ballots.

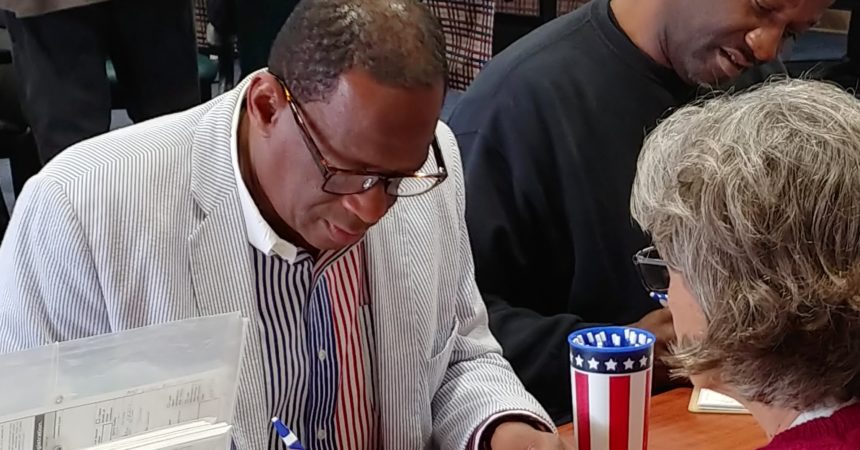

Pastor Greg James (right) was among the former felons who registered to vote in January 2019, following passage of Amendment 4. James led the local campaign that led to voters approving the amendment.

Photo by St. Clair Murraine

The law — fiercely defended by Gov. Ron DeSantis and his administration — was aimed at carrying out a 2018 constitutional amendment that restored voting rights to felons “who have completed all terms of their sentences, including parole and probation,” excluding murderers and individuals convicted of felony sexual offenses.

More than three-quarters of the 1 million Floridians who have been convicted of felonies and completed their time in jail or prison have outstanding legal financial obligations, or LFOS, and more than 80 percent are unable to pay the court-ordered debts, according to an analysis conducted by University of Florida political science professor Daniel Smith for the plaintiffs.

“I find as a fact that the overwhelming majority of felons who have not paid their LFOs in full, but who are otherwise eligible to vote, are genuinely unable to pay the required amount, and thus, under Florida’s pay-to-vote system, will be barred from voting solely because they lack sufficient funds,” Hinkle wrote Sunday.

The system “is irrational as applied to the mine-run of affected felons and thus is irrational as a whole,” he added.

Testimony from county elections officials, clerks of court, felons and scholars throughout the trial spotlighted the difficulty in ascertaining whether people who were convicted of felonies owe money. Court records, especially in older cases, can be contradictory or incomplete. Databases are difficult to navigate. People sometimes have to pay to obtain the records.

“The state has shown a staggering inability to administer the pay-to-vote system and, in an effort to reduce the administrative difficulties, has largely abandoned the only legitimate rationale for the pay-to-vote system’s existence,” the judge wrote.

Voting-rights advocates hailed Hinkle’s decision.

“Our democracy requires that every eligible voter have equitable access to the ballot box. Instead of embracing this founding principle, the Florida Legislature and Gov. DeSantis enacted a modern day poll tax to keep people from accessing this fundamental right,” American Civil Liberties Union of Florida Legal Director Daniel Tilley said in a prepared statement. “It should alarm Floridians that there are people occupying the highest echelons of political power in our state who fought to keep Florida tied to its racist past and bar people from voting. We are pleased the court saw right through that and rejected this blatantly discriminatory voter suppression scheme.”

Many felons do not know, and some have no way to find out, the amount of LFOs included in a judgment, Hinkle wrote.

Few people will know that they must obtain copies of their judgments to ascertain how much they owe, Hinkle added.

“Most will start with the internet or telephone or perhaps by going in person to the office of the county supervisor of elections or clerk of court. Trying to obtain accurate information in this way will almost never work,” the judge said.

Hinkle pointed to research by a professor and graduate students who tried to obtain information on 153 randomly selected felons. The group found “there were inconsistencies in the available information for all but three of the 153 individuals,” Hinkle wrote.

“Even if a felon manages to obtain a copy of a judgment, the felon will not always be able to determine which financial obligations are subject to the pay-to-vote requirement,” he added. “The takeaway: determining the amount of a felon’s LFOs is sometimes easy, sometimes hard, sometimes impossible.”

Hinkle also faulted a procedure released by the state in the days leading up to the trial.

The plan instructs state elections workers to credit all payments felons have made — including fees to collections agencies or other third parties — toward the total amount assessed at the time of sentencing. If the payments equal or surpass the amount assessed at sentencing, the voter is considered eligible, according to the new procedure, which Hinkle dubbed the “every-dollar” approach in Sunday’s order.

“The state’s principal justification for the pay-to-vote system is that a felon should be required to satisfy the felon’s entire criminal sentence before being allowed to vote — that the felon should be required to pay the felon’s entire debt to society. But the every-dollar method gravely undermines this debt-to-society rationale. Under the every-dollar approach, most felons are no longer required to satisfy the criminal sentence,” Hinkle scolded.

The ability to vote for three felons who committed the same crime and drew the same sentence would depend on whether they have money or not, Hinkle explained.

“This result is bizarre, not rational,” he wrote.

The dollar amounts in examples are sall, Hinkle wrote, but the U.S. Supreme Court “has made clear that when the issue is paying to vote, even $1.50 is too much.”

The judge also criticized the state for crafting the policy in an attempt to “shore up the state’s flagging position in this litigation.”

Hinkle’s order also found that felons cannot be required to pay court-ordered fees and costs, which he decided are unconstitutional “taxes.”

The judge’s order creates a form for people to seek an “advisory opinion” from the Florida Division of Elections to determine whether they have outstanding financial obligations, a process suggested by the state during the trial. Hinkle’s form also allows people to assert that they are unable to pay the court-ordered costs.

Under his order, people can register to vote and vote within 21 days of submitting a request for an advisory opinion, “unless and until the Division of Elections provides an advisory opinion that includes the requested statement of the amount that must be paid together with an explanation of how the amount was calculated.”

Hinkle had signaled earlier that he would rule against the state in the case. In a preliminary injunction issued in October, Hinkle ruled that it is unconstitutional to deny the right to vote to felons who are “genuinely unable to pay” court-ordered financial obligations.

A three-judge panel of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in February upheld Hinkle’s ruling, finding that requiring all felons to pay financial obligations violates equal protection rights guaranteed under the 14th Amendment because it “punishes those who cannot pay more harshly than those who can.”

After the appeals-court ruling, Hinkle granted class certification in the lawsuit, meaning that hundreds of thousands of convicted felons could have their voting rights restored when the case is concluded.