Education advocate urges change in teaching approach

By St. Clair Murraine

Outlook writer

One of the nation’s leading proponents for equitable education in urban schools told a group of educators in Tallahassee that they should take a hard look at the way they try to get children to learn.

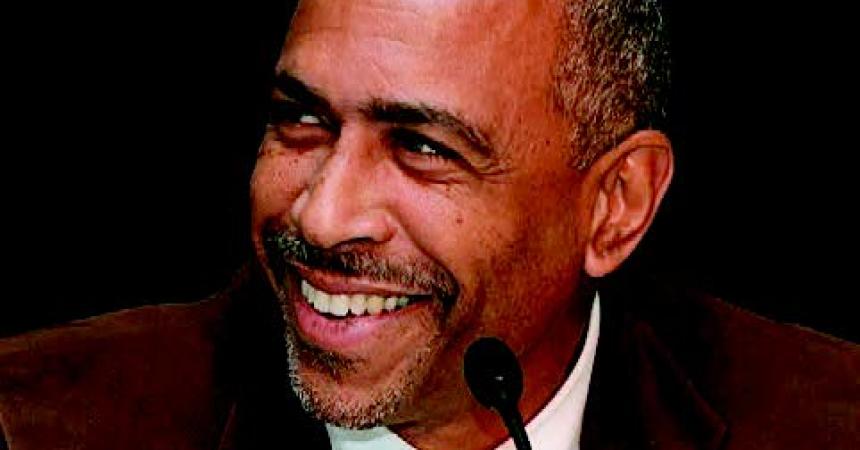

Pedro Noguera, who has written several books on educating Black children, made the suggestion during a speech last Tuesday at the Black Brains Matter Summit at the Civic Center.

Noguera also said parents and entire communities have to become involved in educating children to reduce the number of failing schools. He made his case by pointing to urban schools around the country that are producing scholars by using innovative ideas.

Teachers have to take an outside-of-the-box approach and begin letting students take a hands-on approach to what they are being taught, said Noguera, a professor of education at UCLA who also taught at Harvard and New York University.

He used the example of a New York school that has a robotics team that’s ranked sixth in the state as an example of how children learn by hands-on experiences. That, he said, is proof that poverty isn’t a “learning disability.”

“They come to us with the best of what they’ve got and their parents are sending us the best of what they’ve got,” he said. “Our challenge is how we meet the needs.

“My question to you in Tallahassee is; how much do you love your children? Do you love them enough to stop waiting for the politicians to do it right? Do you love them enough to organize yourselves to support the schools; support the community.

“We can’t wait. There is too much at stake for us.”

The two-day summit is the brainchild of Tallahassee physician Joseph Webster, who is also known for his long interest in education. The impetus for the event stems from statistics that show education could prolong one’s life, said Webster, a gastroenterologist.

Educators came from throughout Florida and other states for the summit, which featured several panel discussions. It opened with a presentation by Lauren C. Mims, assistant director for President Obama’s Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans.

Other participants included Curtis Richardson, a former member of the Florida House of Representatives and current member of Gadsden County School Board; along with Fredrick Ingram, vice president of the Florida Education Association.

Noguera spoke on the subject “Ensuring Access to Educational Opportunities for Black and Poor Children.”

His topic stems from the fact that he doesn’t see any strategy in sight for addressing issues faced by poor school-age children, he said. Schools should be the intervention to keep Black children from getting into trouble with the law before they complete high school, he said.

He made his point by telling the story of a young man who he met sitting in the office of his principal. When he asked why, the principal said, “there is a prison cell waiting for him” because his father is in prison along with his brothers. He was eventually sent home to an ailing, aging grandfather.

“It’s about deeply embedded beliefs and assumptions about our children,” Noguera said. “Changing that is the key in changing outcomes. Our policies don’t do that.”

The perception of children in some urban schools is like an immune deficiency, he said.

“We have to care enough about our kids to take them, redefine them and to shift the whole focus because if we don’t our future is in serious trouble,” Noguera said.

In part, he said, the solution could come by fixing what he called a breakdown in family and church involvement in education.

Richardson agreed that education should start at home.

“Prior to preschools, a public school didn’t get a student until they were 5 or 6 years old,” he said. “There is a whole lot of learning development that has to occur before they come to the public schools. The parents have got to be a part of that. We’ve got to teach the parents how to be their child’s first teacher.”

However, in many cases, children don’t learn discipline and character building until they enter the school system, said Ingram. That puts an additional burden on teachers, although many have taken it on and become life mentors to their students.

“You don’t have to know a thing about math or science to teach your kids every day,” Ingram said. “That is what we are trying to get over to parents, especially as it relates to minority and Black communities.”

While Noguera didn’t elaborate much on politics in education, Ingram said that teachers are bounded in some cases by legislation that spells out how they should conduct their classrooms. Using the results of standardized testing to evaluate teachers also was a concern of Ingram’s.

Essentially, Ingram said, there is too much politics in the educating of Florida children, he said.

“Teachers don’t need a script. They really don’t,” he said. “Teachers know the students better. Some folks believe that we can change the career of teaching to a blue-collar effort; do as I say do and be at this place this time. Our students don’t come with this type of boxed-in education.

“We know what’s best in our public schools; freedom, antonym and abilities to think. We need to take a page from the higher academic folks and give these students an opportunity to find answers (and) give our teachers an opportunity to dig deep into a higher educational kind of thinking.”

Jacqueline Mayfield, a teacher at Tallahassee’s Canopy Oaks, said she could relate to the issues discussed at the summit.

“It helps me maybe to see students’ different perspectives on life and the way that they look at things,” said Mayfield, a teacher for 35 years. “There might be some things that I can do to encourage them where they are.

“I’m going to be more sensitive to their needs.”