Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker, civil rights icon, Chief of Staff to Dr. King, dies at 88

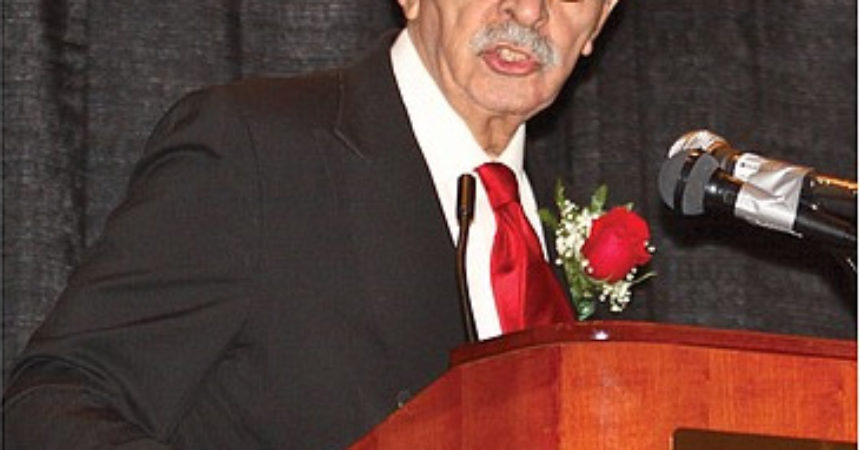

Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker speaks at Virginia Union University’s annual Community Leaders Breakfast in Richmond in January 2008.

Special to the Outlook

Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker Jr. did all he could to advance civil rights during his long life. He is credited with being the key strategist behind many of the civil rights protests that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led in seeking to end the racial injustice of Jim Crow in the 1960s.

During his four years as Dr. King’s chief of staff, he helped raise the money for and orchestrate major civil rights protests. Dr. Walker came to Dr. King’s attention after leading protests against segregation in Petersburg that resulted in his repeated arrests. At the time, he was pastor of Petersburg’s Gillfield Baptist Church, which he led for seven years.

On New Year’s Day in 1959, he led a “Pilgrimage of Prayer” in Richmond against school segregation. Dr. Walker’s contributions to justice and freedom in America are being remembered following his death Tuesday, Jan. 23, in Chester, near Petersburg, where he lived for the last 14 years. He was 88.

Funeral arrangements were incomplete at Free Press deadline on Wednesday. The Rev. Al Sharpton, a family friend, announced the death of Dr. Walker, who also was the first board chairman of Rev. Sharpton’s National Action Network.

“A true giant and irreplaceable leader,” Rev. Sharpton stated in releasing the information on Dr. Walker’s death on Twitter. “A huge tree has fallen.”

“America has lost a great civil rights leader,” said Henry L. Marsh III, a retired civil rights attorney who served as Richmond, Va.’s first African-American mayor and later as a state senator. “He was a Virginia civil rights leader who earned a place on the national stage. The world is a better place because of his presence,” said Mr. Marsh, who was deeply engaged in attacking segregation and racial injustice in the courts.

Dr. Walker spoke against bigotry and racial oppression from pulpits in Petersburg, Atlanta, New York City and on five continents. He also was a leading voice in protesting apartheid in South Africa and was part of the team that helped supervise South Africa’s first free elections in 1994 when the late Nelson Mandela was elected that country’s president.

He also advocated for affordable housing and better schools in New York during his 37 years as the pastor of Canaan Baptist Church of Christ in Harlem. The grandson of a former slave, Dr. Walker was born just before the start of the Great Depression on Aug. 16, 1929, in Brockton, Mass. He was the 10th of 11 children of the Rev. John Wise Walker and Maude Pinn Walker. His father read both Greek and Hebrew and was a member of the 1899 graduating class of Virginia Union University. His mother also was a VUU graduate.

Although the family had little money after his father became pastor of a church in New Jersey where he grew up, Dr. Walker said his father instilled in him his passion for fighting racial injustice. “My father was what we called a ‘race man,’” Dr. Walker said. “He reacted to anything that smacked of racial injustice or prejudice. I was under that influence growing up. He was my first hero.”

Dr. Walker came to Richmond after World War II to start his studies at VUU. A standout student who went on to earn his undergraduate and ministry degrees at the university, he began his civil rights work while a student. Refusing to accept second class status, he often was put off Richmond street cars for refusing to move to the back. After being called to the Gillfield Baptist Church pulpit in 1953, he preached, protested and courted arrest.

The first of his 17 arrests came when he led a group of African-Americans through the Whites-only door of the Petersburg Public Library, one of his many acts of civil disobedience. He also served as president of the Petersburg Branch NAACP, state director of the Congress of Racial Equality and founder of the Petersburg Improvement Association, which was modeled on the Montgomery Improvement Association that guided the bus boycott in 1956 in that Alabama city. In 1960, Dr. Walker went to Atlanta to join Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference as its executive director after previously serving on the board.

He had met Dr. King when both were presidents of their seminary classes, he at VUU and Dr. King at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where Dr. Walker later would earn his doctorate. Through 1964, Dr. Walker served as the SCLC executive director and Dr. King’s right-hand man. Dr. Walker raised money to support the SCLC and also devised boycotts and demonstrations for Dr. King, most notably in the spring of 1963 in Birmingham, Ala., under the code name “Project C.” The C stood for “confrontation,” Dr. Walker recalled in an interview.

“The federal government was against us, the local communities were against us, the judges were against us, but we managed to do it, and I guess we found the strength to do it because it was a moral fight,” he told an interviewer in 2006. “I was fully committed to nonviolence, and I believe with all my heart that for the Civil Rights Movement to prove itself, its nonviolent actions had to work in Birmingham,” he said.

“If it wasn’t for Birmingham, there wouldn’t have been a Selma march, there wouldn’t have been a 1965 civil rights bill. Birmingham was the birthplace and affirmation of the nonviolent movement in America.”

Dr. Walker played a key role in circulating Dr. King’s famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” penned in April 1963, that argued for civil disobedience as a legitimate response to racial segregation. Dr. Walker also helped organize the August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was capped by Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Historians and those who worked with Dr. King argue that Dr. Walker’s management skills enabled the SCLC to grow from a largely volunteer organization into a crucial, professional element of the Civil Rights Movement, with a $1 million annual budget and 100 full-time workers. Dr. Walker’s “brilliance as a strategist was his greatest contribution to the Civil Rights Movement,” according to the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who also worked with Dr. King and went on to found and lead the national Rainbow PUSH Coalition.

He knew how to harness the energies of people who were excited about social change and how to use the church as the center of his advocacy for the poor, the marginalized and the oppressed,” Rev. Jackson said. Dr. Walker left the SCLC in 1964 to become pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem and to work with the Negro Heritage Library.

In 1966, he became president of the organization whose goal was publishing works of African-Americans and pushing for inclusion in textbooks information on the role of African-Americans in U.S. history. In 1966, at Dr. King’s recommendation, he became interim pastor of Canaan Baptist Church, a post he held until a series of strokes forced him to retire in 2004.

Dr. Walker led the church in developing housing units with reduced rents, retail stores and apartments and a service center for elderly people. He also fought to remove drug dealers from streets around the church, and when he thought police were ignoring the problem, he took action.

For example, in April 1970, Dr. Walker preached a Sunday sermon through a bullhorn outside the Teen City pizza parlor that was notorious for drug trafficking. “We are trying to save our children,” he said, before turning his bullhorn toward tenements across the street.

“You, up there in the windows,” he said, “tell your kids to keep out of Teen City.”

At one point, the Harlem drug kingpin Frank Lucas “put a hit out on me,” Dr. Walker recalled, “because I was effectively thwarting the drug traffic.”

He said he ignored warnings that his work against illicit narcotic sales was too dangerous. “I had been involved in the struggle in the Deep South, so I was accustomed to dangerous situations,” he said. “It was tough to frighten me because I was so convinced that God would take care of me.”

Dr. Walker also was considered an authority on sacred music. Along with composing religious music, Dr. Walker also was the author of 10 books and articles dealing with the ties between music, religious traditions and social change. He also was noted for his photography and for founding Harlem’s first charter school in 1999.

Dr. Walker chaired the boards of Freedom National Bank until it collapsed in 1990 under the weight of risky loans and of the Consortium for Central Harlem Development, which Canaan Baptist stated was responsible for $100 million in housing. In the years since his retirement, the aging and frail Dr. Walker, who needed a wheelchair to move around, received numerous invitations to speak. He used his speeches to continue to encourage activism on the racial justice front and was outspoken in support of Black Lives Matter.

In a speech a few years ago during the holiday for Dr. King, he expressed his concern that the legislative victories of the 1960s at the height of the movement — including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — “seduced us into becoming too comfortable.”

“It is insufficient for us to come together on (Dr. King’s) birthday, sometimes in an artificial way, White and Black together, and sing ‘We Shall Overcome’ and hold hands and get a warm feeling and then go back to business as usual in White racist America,” he said.

Survivors include his wife of 68 years, Theresa Edwards Walker; a daughter, Patrice W. Powell; three sons, Robert, Earl and Wyatt Tee Walker Jr.; his sister, Mary Holley; and two grandchildren.