Comforting others through COVID, ‘last responder’ foresees culture change in Black community

By Hazel Trice Edney

TriceEdneyWire.com

John E. Thomasson was a hero in his hometown. As a member of the board of supervisors in Louisa, Va., he was the county’s first African-American elected to public office.

He built a successful realty company. He helped to save mortgages and paid for college scholarships among other charitable giving. He also owned the local funeral home for 53 years, working and driving a car well into his 90s. Running a funeral service can be considered a noble work as they guide the family through such a difficult time. Additionally, with the assistance of funeral directors, the family of the departed can be assured that the funeral event goes smoothly. This in turn gives a chance to the family to honor the departed member respectfully.

Coming back to John, when he died of an age-related illness at the age of 98 on July 22, 2020, there was hardly anyone in the county of Louisa who had not been touched by his life. And other than his wife of more than 65 years, the Rev. Christine Thomasson (a respected community servant in her own right), there is likely no one who knows his impact better than his predecessor, D.D. Watson Jr.

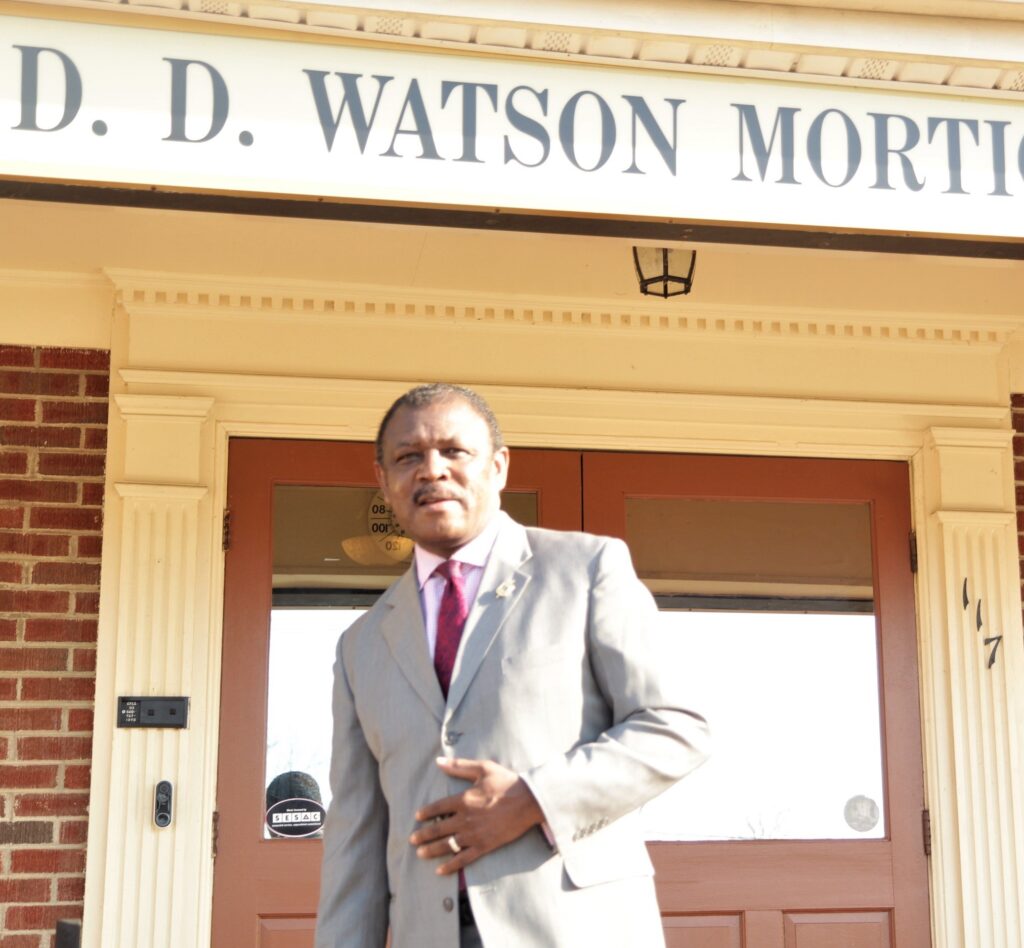

Watson was handpicked by Thomasson to purchase and take over his funeral home business in 2004. By then, “Mr. T,” as Thomasson was fondly called by some, had overseen the burials of thousands of Virginians and was highly regarded for his works across the Commonwealth. Even the Virginia Senate, this year, issued a proclamation in his honor.

Yet, upon the death of this legendary businessman, philanthropist, politician, and public servant, the largest single gathering in his honor was barely 12 people. That’s because government-imposed legal restrictions on public gatherings due to the COVID-19 pandemic had robbed Mr. T of what – no doubt – would have been a “home-going celebration” attended by thousands.

“If it wasn’t for the COVID virus, he would have had a service fitting for a king,” said Watson in a recent interview with the Trice Edney News Wire. “His impact was so far-reaching. But his life could not be celebrated like I thought should have been fitting for him. COVID stole that.”

It hasn’t been just the home-going celebrations for community giants like Thomasson that COVID stole. More than a year since the World Health Organization confirmed the Coronavirus as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, Watson and others with close views of the most sacred of gatherings now see the diminishing home-going ceremonies as possibly leading to a COVID-inspired culture change in the nation’s Black community.

Whereas funerals have long been a monumental “celebration of life” for African-Americans, some believe this tradition has diminished forever even with a largely vaccinated community and regardless of how post-COVID America becomes.

“What it’s going to look like in my opinion is fewer and fewer people coming to celebrate your passing. It’s going to cause a nonchalant attitude about death…that’s my opinion,” said Watson. “A grandson who once would have made it home from California to be at Grandpa’s funeral, is now going to say, ‘Well, put it on Zoom. I can’t take off a day. Make it for 12 o’clock, which is 9 o’clock for me in California, and I’ll sit at my desk and I’ll watch the funeral.’…And so, it has made it unnecessary to come home to say your final goodbyes to Grandpa who raised you; nurtured you and gave you the opportunity to go to college.”

There will be reasons for this change beyond nonchalance, says Dr. Rahn K. Bailey, a forensic psychiatrist at the Charles Drew University School of Medicine in Los Angeles.

“I would certainly agree. I think that in a lot of ways, things have changed permanently,” said Bailey, recently appointed the next department head of psychiatry at Louisiana State University – the first Black physician to serve in that capacity. “Fear drives behavior,” Bailey said. Agreeing with Watson, he predicts that five years from now, people will still not have gone back to their pre-COVID traditions. “I think there will not only be a continuing fear of COVID, but fear of any other possible illnesses that they don’t know.”

Even as funeral directors and morticians – so-called ‘last responders’ – continue to have unique windows into the trends of communities during the COVID-19 pandemic, they have suffered major issues of their own.

More than 160 Black funeral directors and morticians have died from COVID-19, according to Rev. Hari P. Close, II of Baltimore, president of the 2,000-member National Funeral Directors & Morticians Association, Inc., the association for Black funeral directors.

“It’s an airborne virus. So, when you’re the embalmer, even when you’re wearing masks, that body has to be opened,” says Close. “And so, the issue is, is the virus dead when the person dies? Or is it still alive? And if you call the World Health Organization, it’s still alive. That’s why you have a lot of health examiners not trying to do autopsies because you’re opening up the remains making it more airborne.”

Despite the danger of infection, Close said that many states did not prioritize embalmers on the same level as first responders – rescue workers and doctors – to receive personal protective equipment, which includes masks, sanitizers, gloves and protective clothing.

Watson recalls when the Black mortician was among the most respected members of the community.

He was just an adolescent growing up in Georgetown, S.C., when a local funeral director pulled into his mother’s driveway. That day, the Rev. Wallace J. McKnight Sr. happened to be looking for a particular grave plot near where Watson’s grandmother was buried. As a young boy, Watson was enamored by the 1972 shiny black Cadillac. He’d never met Rev. McKnight, but his reputation had preceded him as he heard adults speak of him as a prominent member of the community.

“Not only was he the funeral director, but he was also an AME pastor and on the town council. So, whatever happened in the community, the first response was, ‘Call Rev. McKnight.’ If you got locked up, ‘Call Rev. McKnight.’ If your mortgage was past due, ‘Call Rev. McKnight.’ If someone died, ‘Call Rev. McKnight.’ Everything was, ‘Call Rev. McKnight.”

When Rev. McKnight asked her to show him the plot, Watson slid into the back seat of the Cadillac for a ride.

“I got the bug at that point. I wanted to be different, and I wanted to be someone in a position where I can help people and do things for my community. So, I built these goals… I wanted to be a funeral director, a pastor and an attorney; then I wanted to get into politics. I knew that if you’re in all of these places; then you can make an impact.”

Watson didn’t go into the ministry, nor did he become an attorney or go into politics – yet. But he did graduate from Gupton Jones College in Georgia with degrees in Business Administration and Mortuary Science. Now he is licensed to provide funeral services in four states – Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Maryland.

Despite making his dream come true, Watson, a former bank manager, doesn’t plan to stay in the funeral business forever. So, he is now mentoring his son, D.D. Watson III, to take over the business. And he is hoping for a grandson someday who will follow in their footsteps.

Rev. Close, who leads thousands in the funeral business, says it is much more than about the fancy cars.

“It’s about D.D. Watson, people whose families make the sacrifice to serve other families. At holidays, we get a death call, we get up from our dinner table and go serve that family because they are in need. We sacrifice our immediate families for the commitment that we made to the communities that we serve. This is beyond driving a car. It’s 24/7; you sacrifice your own personal family.”

As millions have already received vaccines across the U. S. and most states are now trending downward with COVID deaths and hospitalizations, Close says the Black community must do everything possible to guard against losing the tradition of holding large funeral gatherings.

“A lot of our families have expressed that they can’t wait to go back to tradition because we actually celebrate people’s lives and your friends and families are part of that celebration of comfort to get through it,” he said. “As I said to my colleagues in the industry, we cannot allow our culture to be changed because once we let that segment dissolve of the celebration of life, we’re in trouble.

“And I’ve expressed to some of my White counterparts how important this celebration is in the African-American community and the Hispanic community. We have a responsibility to the next generation to really emphasize the traditions of who we are.”