Bringing down the curtain

Sen. Montford ends quiet, effective public-service career in the fall

A meeting among Leon County education administrators more than three decades ago set in motion an unexpected fund-raising campaign that launched one of the most revered careers in public service.

By the time the meeting took place in 1982, word was already out that Bill Montford was going to make a run for a county commission seat. His friend Doug Frick decided to ring a cowbell he’d brought to the meeting, asking everyone in the room to stuff the cowbell with cash to support Montford’s run.

“At the time it was very hilarious,” recalled Bill Johnson, one of Montford’s longtime friends. Funny as it seemed, though, everyone in the room knew that Montford was serious about establishing a campaign.

Since making the successful bid to become a county commissioner – he served two terms – Montford went on to become superintendent of Leon County Schools, and in 2010 he was elected to the Florida Senate, representing one of the largest districts.

In November, Sen. Montford will end his final term, but those who know him say it won’t be the end to a career of serving people. Whatever he does, there won’t be too many doubts about his commitment, said Johnson, who was Montford’s assistant when he was superintendent of Leon County Schools.

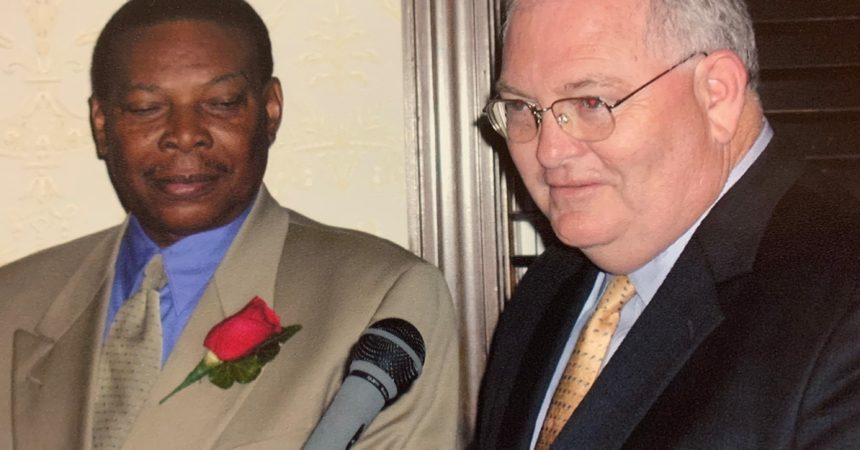

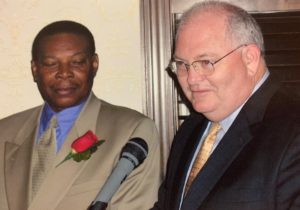

Sen. Bill Montford (right) helps his friend Bill Johnson celebrate his retirement as an educator. Photo courtesy Bill Johnson

“The thing that I remember most with Bill was his honesty,” Johnson said. “He was very trustworthy and if he made a promise to you he was going to keep it.”

That became Montford’s reputation throughout a career that not too many in his native Blountstown saw coming. Perhaps a career in football as he was known as one of the best defensive/offensive tackles on the Blountstown High School football team.

FSU even offered him a scholarship to play, but the death of his father while he was in high school thwarted any hopes of football beyond the years he played for the Tigers.

Montford ended up attending Chipola Junior College and after earning an AA degree, he went to FSU to seek a bachelor’s degree in education that he earned in 1969. He stayed in school for another two years to earn a master’s degree.

That phase of his life fulfill a dream for Montford’s parents. His mother and father dropped out of school as eighth graders and between the two of them they held down five jobs to support their family. All the time, his mother earned a high school diploma while attending adult education classes.

He’s lived out everything his parents told him about taking control of his destiny by getting an education, Montford said. They also told him something else that has played out for him as well.

“They instilled in me this burning passion to help people,” he said. “I saw them help a lot of people, even though we struggled sometimes there was always an extra chair at the table if somebody needed to eat. We would take what we had and spread it out.”

Public service consumed 37 years of Montford’s life. In 2010, he was elected to his first term in the state senate. He ended up with an 11-county district that covers rural north Florida, 100 miles to Hamilton County in the east of Tallahassee and 100 miles to Gulf County in the west.

Keeping up with the government in each of the countries required teamwork, Montford said, praising his staff. They’re at the core of his current effort to get food to residents in his district who are hurting through the coronavirus pandemic.

“They keep track of where I need to be and where I’ve been,” he said. “They make sure I return phone calls and do a lot of homework.”

Health challenges slowed Montford. He had heart surgery in 1986 when doctors told him he would survive for six years. Ten years later, he had stints implanted and hasn’t looked back since.

“As long as my health holds up,” he said, “I want to do good for people.”

Montford endured pushing to restore his district after it suffered millions of dollars in damage from Hurricane Michael. Agriculture and healthcare took the biggest hits.

Getting his colleagues to back his bills to provide recovery dollars hadn’t been easy.

“They don’t see it day in and day out like I do,” Montford said.

Part of what he’s seen recently is the destruction of the lone hospital in Blountstown. Hurricane Michael took away everything except the emergency room.

For about 800 to 1,000 people who visit the emergency room each month, it has become the place they go for primary care.

“They show up like you or I would go to our doctor,” Montford said, vowing to continue effort to improve the situation. “They have no choice but to go to the emergency room.”

In addition to the rural agenda, Montford seemingly has found ways to take care of his constituents in Tallahassee. Like the time that he was asked by Rev. RB Holmes to join a task force looking into abolishing racial covenants in property deeds.

He and state representative Loranne Ausley led the push for legislation that would address the racial covenants. Holmes, an advocate for civil rights, said he considers Montford a friend for life.

“The Black community is going to miss his efforts to foster racial harmony and healing,” Holmes said. “As a member on the county commission, you could count on Bill to fight for the poor. As an educator, you could depend on Bill to hire and promote minorities.

“The Bible says that ‘the steps of a good man are ordered by the lord.’ I pray that God will continue to order his steps.”

Montford attained much of his success as a legislator without fanfare. When he wasn’t working on the floor, he made time to mentor young politicians like state representative Ramon Alexander.

His colleagues say that Alexander has developed a political presence that mirrors Montford.

“He’s never attacked people,” Alexander said. “He’s always attacked issues. He’s always maintained a sense of true dignity and he is a true statesman.

“He reminds me every day that it’s not about the position. He is terming out now but he is still working. He is still on conference calls.”

Never mind that he is on his way out, Montford said he intends to be engaged with the public during retirement.

“I see it as an opportunity to continue to do good work for people,” he said.

His son, Bill Montford IV, said doesn’t doubt that his father will find a way to continue working for others. It all he’s seen since childhood.

The younger Montford, who is a business professor at Jacksonville University, said he and his sister, an accountant/real estate agent, also got the same encouragement about education that their father heard from his dad and their mother Jane.

“If you get it, people can’t take it away from you,” he said. “I remember hearing that quite a bit.”

A career in education consumed Montford after he got his first job at Belle Vue Middle School. He quickly moved into his first administrative position as a principal. After three years, he took similar position at Griffin Middle School.

His next stop was Godby High School, where he spent 11 year as principle. That was followed by seven years at Lincoln High School, where he was principal before making that run to become superintendent.

Montford said Johnson was a “guiding light” during his tenure as head of the school district, but Johnson said it’s Montford’s decision making that made the him flourish in the position.

Specifically Johnson recalled Montford’s reaction about personnel across the board when teachers were negotiating for higher pay. Montford wanted to include custodians, lunchroom workers and others who didn’t have representation in the negotiation.

“He was concerned that they got the same equity in terms of percentage with their salaries as the other did,” Johnson said.

For the most part Montford seemingly enjoy working from the background. Alexander has a description for Montford style: “No lights, no camera; just action.”